Arthroscopic shoulder surgery for shoulder dislocation, subluxation, and instability: why, when and how it is done

Last updated: December 31, 2009

Overview

Shoulder instability (also called subluxation) and shoulder dislocation are potentially painful and disabling conditions, and the treatments for these conditions vary widely depending upon the severity of symptoms and signs. Many patients will improve with the appropriate bracing and physical therapy. However, for those patients who require surgery, arthroscopic shoulder surgery should be used to both define and diagnose the exact nature of the joint instability. In most cases, the problem can be treated using specially-designed instruments working through very small incisions with a minimum of discomfort and without the need for a hospital stay.

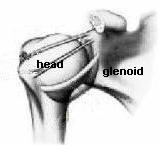

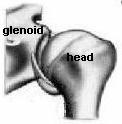

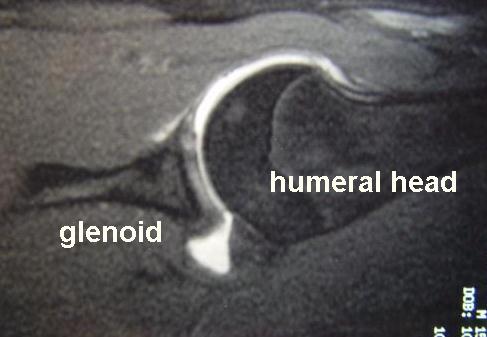

The terms "instability", "subluxation" and "dislocation" mean different things to different people. In addition, the term "shoulder instability" is a term that encompasses a vast spectrum of shoulder problems. In the simplest sense, the shoulder is like a "ball and socket" joint. Figure 1a shows the front view of a right shoulder. Figure 1b shows the view from behind of a right shoulder. For the sake of simplicity, the surrounding muscles and tendons are not shown, but the glenoid (socket) and humeral head are labeled. Figure 2 shows an MRI view looking down through the shoulder joint from above. The glenoid and humeral head are labeled. (Figures 1a and 1b are redrawn from Warner et al. Am J Sports Med 1992:20:675)

Subluxation and dislocation both represent problems that occur when the "ball" (or humeral head) doesn't stay centered correctly in the "socket" (or glenoid). These problems may manifest themselves in a variety of ways; from pain with the normal activities of daily living, to the inability to lift the arm without dislocating the joint, and everything in between.

For many patients, the diagnosis is made in the emergency room after they have dislocated their shoulder during sports or an accident. Many other people who have subtle instability can be misdiagnosed as having "rotator cuff tear" or "bursitis". An experienced shoulder surgeon or sports medicine surgeon can usually recognize the signs of shoulder instability. Often, the diagnosis is confirmed using Magnetic Resonance Imaging techniques (MRI), however many people can have a "normal MRI" appearance and debilitating symptoms—so a thorough clinical examination by an experienced orthopedic shoulder surgeon is recommended. Video 1 shows a patient being examined prior to surgery. The right shoulder can be subluxed out of joint in the anterior direction. Note: Video may be slow to load on non-broadband internet connections. Modem users may wish to right click (or Command click for Macs) and save the file locally for viewing.

For many people, a conservative approach with physical therapy and a home-based strengthening program can resolve the pain or symptoms of instability. Those who do not improve with therapy, high-demand athletes, and overhead workers may require surgery to achieve a functional, painless range of motion. When surgery is required, it is of utmost importance that the surgeon look for and address all the potential causes of instability in the joint. If any of the factors contributing to instability is not addressed, the surgery will fail.

Arthroscopic shoulder surgery, or shoulder arthroscopy is a valuable tool to diagnose and treat shoulder instability and dislocation. Using the scope, an experienced surgeon can evaluate the entire shoulder joint and can usually treat the conditions leading to instability through very small incisions using specially-designed instruments and devices. In a small subpopulation of patients, a formal open surgery (using an incision about 3" to 5" long) will be required to correctly address the problem(s) encountered. The goal of surgery is to re-establish the stability of the humeral head in the shallow glenoid socket without compromising the shoulder range of motion. This is a delicate balance, and the results are most predictable in the hands of a highly-specialized surgical team that is familiar with the various techniques and instruments and who perform the surgery often. Such a team will maximize the benefits of the surgery and minimize the risks. The procedure can usually be performed within a few hours under general (or nerve block) anesthesia, and the patient can be discharged to home with a minimum of discomfort. In addition, the scope allows the surgeon to take pictures and video to show to the patient what problem(s) existed and how the problem was addressed.

Patients undergoing arthroscopic shoulder stabilization require a limited period in a sling (usually 2- to 3-weeks) with some simple range-of-motion exercises at home. They will require fairly intensive outpatient physical therapy for re-establishing pain-free motion and strengthening the shoulder muscles for a few months. Normally, a person can return to most forms of normal activity within 6 weeks, and limited athletics between 10 and 14 weeks. A return to all activities and even contact athletics can usually be accomplished between 14 and 24 weeks, depending on the sport.

a patient being examined prior to surgery

Symptoms & Diagnosis

Characteristics of shoulder dislocation, subluxation, and instability

By definition, all forms shoulder dislocation and shoulder instability share the common bond that the humeral head (or "ball" at the top of the arm bone or humerus) does not stay adequately centered on the glenoid (or "socket" attached to the shoulder blade). This instability can be subtle, manifesting as pain at the shoulder or upper arm with overhead activities; mild to moderate, manifesting as the inability to perform overhead activities without apprehension (or the sense that the shoulder could dislocate); or severe, in which the shoulder can easily dislocate voluntarily or involuntarily during any activities, overhead or otherwise. Figure 3 shows the humeral head dislocated from the glenoid socket (redrawn from Burkhart et al. Arthroscopy. 2000:16:7:682)

A dislocation following trauma (such as a sports injury or auto accident) may be obvious, requiring emergent relocation. However, subtle instabilities can be difficult to diagnose correctly in the hands of physicians who do not normally examine the shoulder. These are not infrequently misdiagnosed as "rotator cuff tears" or "bursitis". In addition, shoulder instability can occur in concert with other shoulder problems, so if the instability is not recognized and treated, the results of a rotator cuff surgery or surgery to remove "bone spurs" may not alleviate the symptoms.

Most patients with significant instability will have the sense that the shoulder "feels like it could come out of joint" when in certain positions, or have the sense that the shoulder "pops out and in" frequently with activities.

Types

The wide range of problems that contribute to shoulder instability can be defined in several ways, including:

- SEVERITY: subtle, mild to moderate, severe (as described above)

- DIRECTION: anterior, posterior, multidirectional

- MECHANISM: traumatic or atraumatic

In fact, the severity, direction and mechanism all influence how the shoulder should best be treated, so all of these factors must be considered.

SEVERITY

In most cases of subtle, mild and moderate forms of shoulder instability, the surgeon may recommend an attempt to stabilize the shoulder through a physical therapy and strengthening program. A certain subset of individuals (contact athletes, overhead laborers, and people who have failed a trial of physical therapy) may require surgery.

Severe shoulder instability, manifested by frequent dislocations and subluxations during normal activities of daily living are less likely to resolve without surgery, but are also most difficult to treat. A subset of patients who may not improve with surgery are those who voluntarily or willfully dislocate their shoulders regularly, or those who are not willing or not able to undergo the appropriate postoperative rehabilitation.

MECHANISM

A shoulder dislocation in a previously "normal" shoulder after an accident, trauma, or a seizure may need to be relocated on an emergent basis in the emergency room. When this occurs, it is advisable that the patient seeks further medical attention with a qualified sports medicine or shoulder surgeon. In persons who have never had problems with the shoulder but then have a traumatic dislocation, a significant injury to the shoulder joint can occur that may result in recurrent episodes of instability or dislocation. Many times, the shoulder can be appropriately braced while it is healing to avoid the need for surgery.

Dislocations and subluxations can also occur in people without any inciting event. This is called atraumatic instability, and can be more difficult to treat. Many people who suffer from atraumatic instability are usually also "double jointed" or "ligamentously lax" in other joints. Because the shoulder is the joint in the human body with the largest range of motion (i.e. it is relatively less stable anyway), the extra laxity or give in the shoulder can predispose it to subluxation or dislocation.

DIRECTION

True dislocations most commonly occur to the front of the shoulder (or anterior dislocation), but can also be to the back (posterior dislocation), or in more than one direction ("multidirectional instability" or "MDI").

The most common direction for dislocation and subluxation (instability) to occur is to the front of the shoulder (anterior dislocation). Anterior dislocations and subluxations are frequently associated with a disruption of the stabilizing ligaments at the front edge of the glenoid (this ligament tear is termed a "Bankart lesion"), but can occur in the absence of any discrete injury as well.

True posterior dislocations are rare, and are usually the result of seizures or major trauma. Posterior subluxation, however, can occur after repetitive athletic trauma, particularly in weight lifters and contact athletes in sports such as hockey, lacrosse, and football.

Persons who have atraumatic instability due to laxity of their shoulder ligaments may sublux or dislocate their shoulder in more than one direction; this is called "multidirectional instability" or "MDI". Multidirectional instability is usually related more to an inherent elasticity in the connective tissues around the shoulder joint, and not to a discreet injury to any particular ligaments of the shoulder capsule. Physical therapy is the mainstay of treatment for mild multidirectional instability (MDI). More severe MDI may require surgery if a patient is to maintain an active lifestyle.

Similar conditions

Unless a true dislocation occurs that must be relocated in the emergency room, the presentation of shoulder instability can be subtle, and the diagnosis can be confused with several other conditions. Instability of the shoulder joint can lead to shoulder pain or apprehension (the avoidance or of overhead activities due to a sense that the shoulder could dislocate). However, there are many other causes of pain and apprehension in the shoulder, including rotator cuff tears, shoulder arthritis or degenerative changes, or impingement (friction between the top of the rotator cuff and bone spurs at the bony roof of the shoulder joint). Not uncommonly, these different problems can occur simultaneously (i.e. instability can lead to arthritis or to rotator cuff tears or to impingment, and alternatively a rotator cuff tear can lead to subtle instability). For these reasons, a comprehensive shoulder examination by an experienced physician is important.

Incidence and risk factors

The shoulder joint had the greatest range of motion of all the joints in the human body and every individual is unique in terms of the amount of ligamentous laxity (or flexibility) they have. For this reason, the "stability" of the shoulder joint is relative from person to person and shoulder to shoulder. In general terms, in the "normal" shoulder the humeral head (ball) should not travel more than a few millimeters in any direction from the center the glenoid (socket)—it should behave essentially as a "ball and socket joint".

"Instability" of the shoulder joint should therefore be defined as excessive motion of the head away from the center of the socket (glenoid) that produces pain or the inability to perform activities of daily living, overhead motions, or sports. The same degree of movement causing symptoms in one person may be perfectly acceptable to another. It is therefore difficult to give an exact percentage of persons who suffer from any particular form of instability.

Once a young person (who is still growing) suffers a shoulder dislocation, it is statistically likely that they will dislocate again. Studies have shown that when a dislocation occurs in a child with open growth plates, there is up to a 100% chance that they will dislocate again. In young adults (after the growth plates begin closing but younger than 20 years old), the re-dislocation rate is about 55% to 95%. People who suffer their first dislocation after 30 or 40 years of age are much less likely to suffer another dislocation without a significant traumatic event (usually less than 10% to 15%). Unfortunately, older persons who dislocate their shoulders may develop other problems as a result of the dislocation, such as fractures at the joint or rotator cuff tears.

Risk factors for shoulder instability include:

- ligament laxity ("double jointed")

- a history of previous subluxation/dislocation of the shoulder joint

- young persons (younger than 20 years old)

- overhead or throwing athletes (baseball, tennis)

- contact athletes (football, hockey, wrestling, lacrosse)

Diagnosis

A physician can diagnose shoulder instability by reviewing the patients history, performing a thorough physical examination and shoulder examination, and through the use of imaging techniques such as X-rays and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

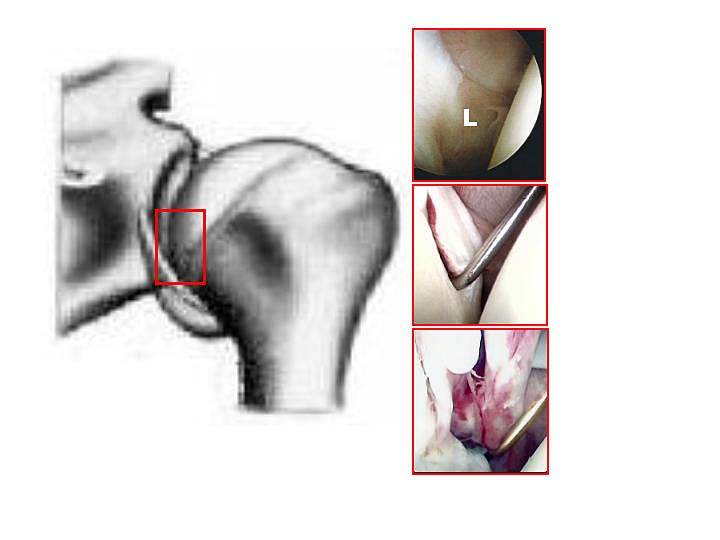

The physical examination and history remain the most reliable means to diagnose instability, because several persons will have no abnormalities present on X-ray or MRI. X-rays may show bony injuries to the glenoid socket (termed a "bony Bankart lesion") or to the humeral head (termed a "Hill-Sach's lesion"). MRI may demonstrate tears of the stabilizing ligaments of the shoulder joint (termed "labral tears", "capsular disruptions" or "soft tissue Bankart lesion". Alternatively, the MRI may demonstrate an abnormally large or "loose" shoulder capsule (joint). Figure 4 shows an MRI of an unstable shoulder. The stabilizing ligaments are torn from the front of the glenoid (arrow). Figure 5 shows an arthroscopic view of the ligament attachments (L) the metal probe is on the labrum, where the ligament attaches. The top view is a normal attachment, the middle is a mild tear, below is a severely torn ligament attachment.

Treatments

Medications

There are no medications that can treat the excess laxity or instability of the shoulder joint. However, some medications such as Non-Steroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) will frequently help to ease pain or symptoms related to the unstable shoulder. These medications can be quite helpful, but can also have side effects and therefore should be taken under the supervision of a physician experienced in their use. Injections of steroids (cortisone) or lubricants (such as hyaluronic acid) into the shoulder have little role in the treatment of instability and carry some risk of infection.

For any medications taken, patients should learn:

- the risks, possible interactions with other drugs

- the recommended dosage

- the cost

Exercises

The stability of the shoulder joint is dependent upon a balance of several factors, including:

- the fit or conformity of the humeral head ("ball") to the glenoid ("socket")

- the integrity of the lip of tissue around the glenoid socket (also called the labrum)

- the integrity of the ligaments within the shoulder capsule that act as "check reigns" to motion (termed the glenohumeral ligaments)

- a "vacuum effect" of the head in the glenoid socket

- the stabilizing effect of the rotator cuff muscles around the shoulder joint

Of all these factors, the one that can be addressed most easily is the strength and function of the rotator cuff muscles. Frequently, the extra laxity of the shoulder joint capsule can be overcome by strengthening the muscles around the joint that are used to stabilize the humeral head in the glenoid socket. These muscles can be strengthened effectively with a supervised and home physical therapy program designed to selectively balance and strengthen the four muscles around the shoulder that comprise the "cuff" ( called the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, subscapularis). Most general shoulder exercisers in the gym do not adequately isolate and address rotator cuff strengthening, so it is important to learn which exercises are most beneficial.

If the exercises are performed gently several times per day on an ongoing basis, many patients will obtain relief of their symptoms and suffer few or no episodes of instability. It is important for patients to learn the possible risks of physical therapy as well as its cost. The anticipated effectiveness of physical therapy is dependent upon the degree and nature of the instability.

Possible benefits of arthroscopic shoulder surgery

In persons who have recurrent episodes of shoulder subluxation or dislocation who continue to have instability despite an adequate trial of physical therapy, surgical stabilization of the shoulder is the most effective method to restore comfort and eliminate the symptoms.

A qualified shoulder surgeon can isolate the factors contributing to instability, including tears of the glenoid socket "lip" (or "labrum"), tears of the shoulder capsule and ligaments, bony fractures of the glenoid socket or humeral head, the integrity of the rotator cuff tendons, or excessive laxity or volume of the shoulder capsule. Video 2 shows a short "diagnostic arthroscopy" of the shoulder, a virtual tour around the joint. This person has a normal glenohumeral ligament attachment, but a partial-thickness rotator cuff tear. Video 3 shows the "diagnostic arthroscopy" in which the ligament attachments at the front of the shoulder are torn. There are different procedures to address each of these problems, and most can be done on an outpatient basis using the arthroscope and special instruments designed to be used through very small incisions (3 to 4 incisions about 1-cm long). Note: Videos may be slow to load on non-broadband internet connections. Modem users may wish to right click (or Command click for Macs) and save the file locally for viewing.

The overwhelming majority of patients who undergo arthroscopic shoulder surgery to address shoulder instability will have a successful result without recurrent problems with subluxation, dislocation, or pain.

Watch Videos:

Video 2 - A short "diagnostic arthroscopy" of the shoulder

Video 3 - The "diagnostic arthroscopy" in which the ligament attachments at the front of the shoulder are torn

Who should consider arthroscopic shoulder surgery?

Arthroscopic or open shoulder surgery is considered for instability when:

- the episodes of instability represent a significant problem for the patient, and inhibit his or her ability to perform the activities of daily living, overhead activities, or sporting activities

- the patient is sufficiently healthy to undergo the procedure

- the patient understands and accepts the risks and alternatives to the procedure

- the patient has truly exhausted non-operative treatments, like physical therapy

- an appropriate and comprehensive diagnostic evaluation has been performed and the nature of the problem is clear

- the patient does not willfully or voluntarily dislocate their shoulder

- the surgeon is experienced and familiar with several techniques and treatments for shoulder instability, including arthroscopic surgery and open (traditional surgery)

- the patient is capable and willing to undergo a comprehensive post-operative rehabilitation (physical therapy) program

The results of arthroscopic and open shoulder stabilization procedures are most effective when the patient follows a simple post-operative rehabilitation program. Thus, the patient's motivation and dedication are important elements of the partnership.

What happens without surgery?

Persons who subluxate or dislocate their shoulder on a frequent basis (on a weekly or daily basis) may lose valuable time from work, progress to more frequent subluxations or dislocations, or worse: do permanent damage to the shoulder joint or develop premature arthritis.

It is impossible to know if a person who suffers a single dislocation or subluxation will continue to have this problem. Persons who are young (less than 20 years old) are likely to suffer from recurrent events. Persons who are older (older than 40 years old) are unlikely to have recurrent events. However, it is advisable to have the shoulder evaluated after any significant event of instability to be sure that there has been no significant damage to the joint. After an initial dislocation or subluxation, an experienced surgeon will usually recommend bracing and physical therapy to try and limit the possibility of recurrence.

Surgical options

Several options are available to the patient and the surgeon, depending on the problem that causes the instability. In most cases, the problem to be treated will dictate the nature of the surgical procedure performed. In the hands of a surgeon who is experienced with arthroscopic shoulder surgery, almost all of the following procedures can be performed alone or together to restore joint stability and eliminate pain using arthroscopic techniques:

- labral repair (anterior or posterior)

- repair of the capsular ligaments (Bankart repair)

- repair of the rotator cuff

- repair of the biceps anchor or SLAP lesion

- tightening of the shoulder capsule (capsulorraphy or capsular shift)

Patients who have large bony fractures at the glenoid socket or humeral head ("bony Bankart lesions" or "Hill-Sach's defects) or those who have true multi-directional instability (MDI) may require an open procedure (using a larger incision) to adequately stabilize the shoulder.

Effectiveness

In the hands of an experienced surgeon, shoulder stabilization can be very effective in eliminating instability and restoring comfort and function to the shoulder of a well-motivated patient. The greatest benefits are often the ability to perform the usual activities of daily living, overhead activities, and sports without the fear of subluxation, dislocation or pain. As long as the shoulder is cared for properly and subsequent traumatic injuries are avoided, the benefits on stabilization should be permanent.

Urgency

A dislocated shoulder (one that is "out of joint") must be relocated on an emergent basis. Any patient who thinks they have had a dislocation, or who can not move the shoulder appropriately after an injury must be evaluated in the emergency room as soon as possible to avoid a possible permanent injury to the nerves or blood vessels around the shoulder. Most often, the dislocated shoulder can be relocated into the joint with a mild sedative in the emergency room. X-rays must be taken to confirm that the shoulder has been appropriately relocated.

Unless the shoulder can not be relocated or is stuck "out of joint", surgical shoulder stabilization is not an emergency. The relocated shoulder is likely to remain in the joint as long as the patient is willing to wear a sling or brace and avoid motions that create un "unstable" feeling. Many persons who suffer their first episode of instability (particularly persons over the age of 30-40 years) may never require surgery to have a fully-functional, stable shoulder after an adequate period of bracing and physical therapy. Persons who suffer frequent or multiple dislocations may wish to have surgery to stabilize the shoulder, but such patients have time to adequately become informed about the surgical options and select an experienced surgeon.

Before surgery is undertaken, the patient needs to:

- be in optimal health

- understand and accept the surgical alternatives, options, risks and benefits

- have discussed and or attempted non-operative measures to treat the problem (i.e. rehabilitation/physical therapy)

- have undergone a comprehensive examination, X-ray and usually MRI work-up to define the factors contributing to the problem

Risks

The risks of arthroscopic or open shoulder stabilization procedures include but are not limited to the following: Infection, temporary or permanent injury to the nerves and blood vessels around the shoulder, excessive stiffness of the joint, recurrent instability or loosening of the joint, recurrent tears of the rotator cuff, pain, allergic reactions to any implants or suture materials used to stabilize the joint, the need for additional surgeries. The anesthesia used during the procedure also has some risks, that can be addressed by the anesthesiologist. The experienced and cautious surgical team uses special techniques to minimize all the above risks. Adverse events following shoulder surgery are extremely rare, but they can not be completely eliminated.

Managing risk

Many of the risks of surgical stabilization can be effectively managed if they are promptly identified and treated. Infections may require a wash-out of the joint, and rarely require removal of any implanted materials. Blood vessel or nerve injuries are rare, and most resolve spontaneously. Occasionally, such an injury may require surgical repair. Excessive stiffness of the joint is rare in the person who is cooperative with the postoperative rehabilitation program, and most of the stiffness will respond to exercises. Excessive laxity or loosening of the joint is a sign that the surgery has not completely addressed the instability, and may require further evaluation and management. If a patient has questions or concerns about the "normal" course after surgery, the surgeon should be informed as soon as possible and be available to explain the expected course and outcome.

Preparation

Surgical shoulder stabilization is considered for healthy and motivated individuals in whom instability interferes with shoulder function and activity.

Successful surgery depends upon a partnership between the patient and the experienced shoulder surgeon. Patients should optimize their health to prepare for surgery. Smoking should be stopped one month prior to surgery, and be avoided altogether for at least three months following surgery. Any heart, lung, kidney, bladder, tooth, or gum problems should be managed before the shoulder surgery. Any active infections will delay elective surgery to optimize the benefit and reduce the risk of shoulder joint infection. The surgeon should be made aware of any health issues, including allergies and non-prescription and prescription medications being taken. Some medications will need to be held or stopped prior to surgery. For instance, aspirin and anti-inflammatory medications (Advil®, Motrin®, Alleve®, and other NSAIDs) should be discontinued as they will affect intra-operative and postoperative bleeding.

Before surgery, patients should consider the limitations, alternatives and risks to surgery. Patients must recognize that the procedure is a process and not an event: the benefit of the surgery depends a large part on the patient's willingness to apply effort to rehabilitation after surgery.

Patients must plan on being less active and functional for 12 to 16 weeks after the surgery. Driving, shopping and performing overhead chores, lifting, and repetitive arm activities may be difficult or impossible during this time. Plans for the necessary assistance need to be made before surgery. For individuals who live alone or those without readily-available help, arrangements for home help should be made well in advance.

Timing

Unless the shoulder is dislocated or stuck "out of joint"; shoulder stabilization surgery can be delayed until the time that suits the patient best. Persons who suffer several subluxations or dislocations on a daily or weekly basis risk further injuries to the shoulder joint or capsule that could compromise the surgical result.

Costs

The surgeon's office should provide a reasonable estimate of:

- the surgeon's fee

- the hospital fee, and

- the degree to which these should be covered by the patient's insurance

Surgical team

Shoulder stabilization, particularly when done through the arthroscope is a technically demanding procedure that must be performed by an experienced, specially trained shoulder surgeon in a medical center accustomed to performing complex arthroscopic shoulder procedures on a weekly basis. Patients should inquire as to the specific training the surgeon has undergone to perform such procedures (i.e. a fellowship-trained, sports medicine specialist familiar with arthroscopic techniques and equipment) and also as to how many of these procedures the surgeon and the medical center perform on a yearly basis.

Finding an experienced surgeon

While surgeons who are capable of performing simple arthroscopic procedures are relatively easy to find, complex reconstructive surgeries in the shoulder (like arthroscopic stabilization procedures and arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs) demand a degree of highly-specialized training. Many capable surgeons will have completed a fellowship (additional year or two of training) specifically in arthroscopic techniques, shoulder surgery and sports medicine. A qualified sports medicine surgeon should be comfortable with both open (traditional) and arthroscopic techniques, and tailor the appropriate treatment to the problem to be addressed. Fellowship-trained surgeons may be located through university schools of medicine, county medical societies, or state orthopedic societies. Other resources include professional societies such as the American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) or the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeon's Society (ASES).

Facilities

Arthroscopic shoulder stabilization is usually performed in a qualified ambulatory surgical center or major medical center that performs such procedures on a regular basis. These centers have surgical teams, facilities, and equipment specially designed for this type of surgery. For those patients who require an overnight stay, the centers have nurses and therapists who are accustomed to assisting patients in their recovery from shoulder stabilization.

Technical details

Shoulder stabilization, either arthroscopic or through an open incision is a highly technical procedure; each step plays a critical role in the outcome.

After the patient is comfortably positioned in a seated position and anesthetic has been administered, the shoulder is given a sterile washed and draped for surgery. The surgeon begins by examining the shoulder while the patient is asleep or the shoulder relaxed so he or she can assess the relative stability of the joint, the range of motion, and feel for any abnormal grinding or catching of the joint.

Next, one or two very small (1cm) incisions, or "portals" are made, usually one in the front and one behind the shoulder joint. Through these small portals, hollow instruments called "canulas" are placed that irrigate the inside of the shoulder joint with sterile saline and "inflate" the joint with clear fluid. The canulas allow the placement of an arthroscopic camera and specially designed instruments within the shoulder joint. Figure 6 shows the 2 healed incisions several weeks following an instability repair.

The surgeon maneuvers the camera around the joint while he or she watches a video monitor of what the camera "sees". A highly-skilled surgeon can evaluate all of the important structures within the joint, test their stability and integrity, and look for signs of ligament injuries, cartilage wear (or arthritis), and bony injuries that can be caused by or lead to shoulder instability or dislocation. (see video 2) Most often, the surgeon will take photographs of the interior of the joint to help to explain to the patient what was found, and how it was corrected. This portion of the surgery is called a "diagnostic arthroscopy" and is absolutely necessary to assure the success of any surgical procedure for shoulder instability (even if an MRI had been obtained prior to the procedure). This is because the arthroscopic examination of the joint is still the "gold standard", or best way to understand ALL of the factors that could be present and may need to be addressed to treat the problem.

Once the surgeon understands what structures within the joint are injured or torn, he or she will choose the best possible surgical approach to treat the problem. A highly-skilled surgeon who is comfortable with the anatomy of the joint and who has exceptional skills with specially-designed arthroscopic instruments and implants can usually address the problem without the need for large incisions.

For the most common types of shoulder instability or dislocation, the ligaments at the front of the shoulder that hold the head in the glenoid socket are torn or loose from the lip of the glenoid (or labrum). Using special implants called "suture anchors" the surgeon can repair the ligaments and labrum in place and tighten them as necessary. These anchors are buried into the bone, and most are made of absorbable materials that will disintegrate over time after the shoulder has healed. Figure 7a shows the labrum (L) torn away from the glenoid surface. Figure 7b shows the labrum (L) repaired to the glenoid using three suture anchors.

Other injuries, such as tears of the origin of the biceps muscle tendon (called a SLAP lesion) can also be seen and addressed during the procedure. Figure 8a shows the biceps (bi) and labrum torn away from the top of the glenoid. Figure 8b shows the biceps (bi) and labrum repaired to the labrum using a suture anchor.

Very rarely, a patient will have severe dislocation is multiple directions (multidirectional instability or MDI) and will require an "open" approach to the shoulder joint through and incision in the front (or in very rare cases, in the back) of the joint. This incision is made in such a way to access the joint without damaging the important deltoid or pectoralis muscles that are important for the shoulder's power. The open surgical approach requires that one of the rotator cuff muscles be moved or split to access the joint and repaired after the procedure is completed. During this open approach, the capsule of the joint is tightened by repositioning the excess or loose ligament tissue into a more suitable position, akin to making a pleat in a pant. The indications for open shoulder stabilization procedures differ according to the degree of instability, and the comfort level and skill of the surgeon with arthroscopic approaches.

At the conclusion of the procedure, any incisions are closed using absorbable or removable sutures. Frequently, a surgeon will insert a temporary, easily-removable catheter (a tiny, flexible plastic tube) into the shoulder joint that is connected to an automatic pump filled with anesthetic solution. This "pain pump" can help considerably with postoperative discomfort, and is removed by the patient or their family 2 or 3 days after surgery. The patient's shoulder is placed into a postoperative sling to protect the shoulder during the early postoperative period.

The absorbable "suture anchors" or implants are gradually absorbed and the sutures attached are incorporated into the healing tissues. When metallic anchors are used (a matter of surgeon preference), these are buried in the bone, and do not affect the integrity of the bone or the shoulder joint. Further surgery is NOT normally required to remove the suture anchors after healing.

Anesthetic

Arthroscopic and traditional open shoulder stabilization procedures may be performed under a general anesthetic or under a brachial plexus regional block that makes the shoulder and arm numb during and for several hours after the procedure. The patient may wish to discuss their preferences with the anesthesiologist prior to surgery.

Length of arthroscopic shoulder surgery

The procedure takes approximately 2 to 2 1/2 hours, however, the preoperative preparation and postoperative recovery can easily double this time. Patients usually spend 1 or 2 hours in the recovery room. Patients who undergo arthroscopic procedures almost always are comfortable enough to be discharged home. Those undergoing more traditional open procedures may require one night's hospitalization.

Pain and pain management

Recovery of comfort and function following shoulder stabilization procedures continues over a few months. Initially, the shoulder must be protected from overuse or stressing the repair while the shoulder heals using a sling and a very strict rehabilitation program. Ironically, many patients who undergo arthroscopic procedures feel very comfortable long before the healing has taken place, probably because the approach spares the patient from large incisions and dissection through the muscle tissues.

Immediately postoperatively, the patient is given strong medications (such as morphine or Demerol) to help with the discomfort of swelling and the work of the surgery. Frequently, at the end of the operation a surgeon can insert a temporary, easily-removable catheter (a tiny, flexible plastic tube) into the shoulder joint that is connected to an automatic pump filled with anesthetic solution. This "pain pump" can help considerably with postoperative discomfort, and is removed by the patient or their family 2 or 3 days after surgery. Most patients are discharged to home with a prescription for oral pain medications (such as hydrocodone or Tylenol with codeine) and an anti-inflammatory medication. After the "pain pump" is removed 2 or 3 days after the operation, the oral medications alone are sufficient for occasional discomfort.

Use of medications

Immediately postoperatively, pain medications are given through an intravenous (IV) line. Patients who require a hospital stay are placed on patient controlled anesthesia (PCA) to allow them to administer their own medication as it is needed. Most patients will go home with a "pain pump" catheter in place connected to an automatic pump that will administer pain medication directly into the shoulder at a constant rate for 2 or 3 days. Oral pain medications are rarely required after the first week or two following the procedure.

Effectiveness of medications

Pain medications are very powerful and effective. Their proper use lies in the balancing of their pain-relieving effect and their other, less desirable effects. Good pain control is an important part of appropriate postoperative management.

Important side effects

The medication in the "pain pump" has a similar effect to the medications used by the dentist during dental procedures—it "numbs" the shoulder joint slightly so that the pain is minimal. These medications have few side effects, and do not cause drowsiness or gastrointestinal side effects.

Other pain medications (taken through the IV or orally) can cause drowsiness, slowness of breathing, difficulties in emptying the bladder or bowel, nausea, vomiting, itching, or allergic reactions. Patients who have been on pain medications for a long time prior to surgery may find that the usual doses of pain medication are less effective. For some patients, balancing the benefits and side effects of medications is challenging. Patients should notify their surgeon if they have had previous difficulties with pain medications or pain control.

Hospital stay

Most patients will not require a hospital stay after a shoulder stabilization procedure, particularly if done through the arthroscope. Generally, a person must spend an hour or two in the recovery room until the anesthetic medication has worn off. The instructions for the care of their shoulder, bathing, use of medications, and potential problems are explained to the patient and their family prior to discharge.

Recovery and rehabilitation in the hospital

When the patient is ready for discharge they should have been explained:

- What home exercises are appropriate and how often to do them

- How and when to remove the "pain pump" (if it has been inserted)

- How to take their medications

- When and how to remove the postoperative dressing

- How to use their postoperative sling

- How to care for their shoulder and incisions

- How to recognized potential problems, and what is normal and abnormal

- Who to call if there is a question

Because fluid is used to expand the shoulder joint during arthroscopic procedures, the shoulder is frequently swollen for a few days following surgery. Also, the incisions will "weep" fluid for a couple of days postoperatively, and the dressing can become damp.

The patient is asked to refrain from using the shoulder and arm EVEN IF IT FEELS GOOD for 3 to 4 weeks after the procedure and remove the sling only to perform a strict set of limited exercises of the wrist, elbow and shoulder. These exercises will be explained prior to discharge.

Some patients find that finding a comfortable position to sleep can be difficult for the first few days. Some tricks to help sleeping are to:

- Try sleeping in a semi-reclined position or recliner chair

- When lying down, support the elbow from behind with one or two pillows so it doesn't fall back against the bed

- The patient should not sleep on their side or stomach

For the first 3 or 4 weeks, a home program of rest and limited self-therapy is usually recommended. Then, as healing has progressed, the arm is removed from the sling and a formal rehabilitation program is started with the physical therapist, on an outpatient basis.

Physical therapy

Some early motion is important after shoulder stabilization, but unrestricted motion can endanger the success of the procedure. For the first 3 or 4 weeks, the patient is scheduled to see a physical therapist once or twice per week to monitor the progress of healing and to reiterate the proper exercises.

After a few weeks, the sling is removed, and a more comprehensive rehabilitation program is started. During this period, the therapist works closely with the patient to re-establish a normal range of motion. The therapist and patient work together, but the patient is expected to do "homework" on a daily basis so that constant improvement is achieved. Once a normal range of motion is re-established, shoulder strengthening is started. It takes about 12 weeks before the shoulder is completely rehabilitated for the normal activities of daily living, and about 16 weeks before contact athletics, throwing, and overhead sports can be re-started. A good therapist can work with the patient on "sports-specific" training to re-train the muscles and shoulder for golf, tennis, throwing, and swimming.

Rehabilitation options

The results of physical therapy are optimized by a competent therapist, familiar with the procedure and the usual expectations, and a compliant patient, who is responsible to do home exercises and is motivated to improve. Most surgeons have a standard "protocol" that they can give to a physical therapist to let them know how to rehabilitate the shoulder. It is important for a patient to find a therapist with flexible hours and in a convenient location because the therapy will become part of a routine for 3 to 4 months. The surgeon can recommend a therapist or therapy group with whom he or she is used to working and who is familiar with the procedure. Therapy is generally done on an outpatient basis, with 2 or 3 visits per week so that the therapist can check the progress and review or modify the program as needed to suit the individual.

Usual response

Patients are almost always satisfied with the range of motion, comfort and function that they achieve as the rehabilitation program progresses. The sense of "apprehension" or pain with overhead motions is usually eliminated. Occasionally, persons will have slight decreases in their overall overhead mobility, as the shoulder has been tightened. These minimal decreases usually do not affect the ability to perform overhead activities or prohibit a return to athletics at the same or a higher level. Figure 9 shows a patient who presented with recurrent dislocations and subluxations after an initial traumatic shoulder dislocation. The figures show her range of motion following the repair of the stabilizing ligaments and rehabilitation of her right shoulder. Despite her active lifestyle and rigorous occupation, she has not suffered any further events of shoulder instability.

If the exercises remain or become painful, difficult, or uncomfortable, the patient should contact the therapist and surgeon promptly.

Risks

There are very few risks to appropriate postoperative therapy. If the therapist and surgeon are not in communication about what exactly what was done and what the short and long term expectations are following this procedure, the therapist can be too aggressive or alternatively too timid about the rehabilitation. This can result in failure of the procedure (re-dislocation or subluxation) or excessive shoulder stiffness. It is exceedingly uncommon for these problems to occur.

Duration of rehabilitation

Every patient is slightly different. Once the range of motion is acceptable and the strength has returned, the exercise program can be cut back to a minimal level. Patients who have special needs, such as overhead athletes, swimmers, overhead laborers, and throwers may require sports-specific training with a therapist or athletic trainer.

Returning to ordinary daily activities

In general , patients are able to perform gentle activities of daily living with the operated arm at the side starting 2 or 3 weeks after surgery. Most persons who work at a desk job can return to work during this time. The patient is strongly encouraged to continue wearing the sling at all times for the first 3 to 4 weeks to remind themselves (and others) that the shoulder is injured and healing, and to limit overhead activities.

Driving should wait until the patient can perform the necessary functions comfortably and confidently, and the pain in the shoulder is at a minimum and pain medications are not required. A good question to ask a patient is "Would you want you driving if your 4-year old child was in the car or playing in the street?" In general it may take longer for a person to drive after the right side has had the procedure because of the increased demands on the right arm for shifting gears, etc.

With the consent of their surgeon, a patient may return to activities such as swimming, golf and tennis between 4 and 6 months following the procedure. More extreme sports (wrestling, pitching, rock climbing, etc) should only be undertaken when the shoulder is extremely comfortable, and the strength is within 90% of the opposite side.

Long-term patient limitations

Patients must avoid impact activities (chopping wood, contact sports, sports with risk of falls) and heavy lifting (overhead labor, lifting heavy weights) until after the strength has returned to normal. Occasionally, the extremes of motion overhead and behind the back or head may be limited because the shoulder joint has been tightened. These limitations almost never affect daily activities and usually do not impact a return to sports at or above the level achieved before the shoulder became unstable.

Costs

The surgeon and therapist should provide the information of the usual cost of the rehabilitation program. Most insurances will cover the costs of some or most of the rehabilitation, except perhaps a "copay" that the patient must pay at each visit. Careful adherence to the home exercises between visits will usually decrease the overall number and frequency of visits required.

Summary of arthroscopic shoulder surgery for shoulder dislocation, subluxation, and instability

THE FIVE THINGS ONE NEEDS TO KNOW ABOUT ARTHROSCOPIC OR OPEN SHOULDER STABILIZATION/CAPSULORRAPHY OR SURGERY FOR THE DISLOCATING/SUBLUXING SHOULDER

- There are many different causes of shoulder instability, from a sense that the shoulder is "loose" to pain to frequent dislocations.

- Many types of instability can be treated non-operatively, with a comprehensive therapy program to strengthen the muscles around the shoulder.

- In some cases, surgery is required to restore function and eliminate pain or apprehension about the joint. The experienced, specially-trained shoulder surgeon can usually treat this problem using specially-designed instruments through tiny arthroscopic incisions. Occasionally, an open approach with larger incisions is required.

- The surgery must be perceived as a process, not an event: there is a strict postoperative regimen that must be closely followed to assure the success of the procedure.

- In most cases, the combination of therapy or an outpatient surgical procedure done through the arthroscope will re-establish a functional, comfortable range of motion without instability and allow a person to return to normal overhead activities and even overhead sports and activities such as golf, tennis, and throwing sports.