Anterior Cruciate Ligament Tears and Their Treatment: Arthroscopic and Minimally-Invasive Surgery for ACL reconstruction

Edited By Albert O. Gee, M.D., Associate Professor, UW Orthopaedic Surgery & Sports Medicine

Last updated: January 24, 2013

Overview

Tears or 'ruptures' of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) are common injuries in athletes of different ages and activity levels. ACL tears are treatable using arthroscopy and minimally-invasive surgical techniques. The surgical success rates for ACL reconstruction exceed 95%. The anterior cruciate ligament is one of the major supportive ligaments in the knee. It extends from the lower leg bone (tibia) to the thigh bone (femur) at the knee. This ligament provides knee stability by preventing excessive forward movement of the tibia in relation to the femur and is also important in controlling rotation of the two bones.

While the ACL is not the most commonly injured knee ligament, tears of this ligament frequently lead to chronic knee instability or “giving way”. ACL tears most commonly result during athletics from vigorous cutting, landing, deceleration or twisting injuries. It is less common for ACL tears to occur as a result of physical contact or collisions during athletics.

Many patients who suffer an ACL tear will know immediately that something “feels wrong” with the knee. Many patients report feeling or hearing a “pop” associated with pain and a sense of the knee “giving out”. The joint will typically swell within several hours which results in restricted motion of the knee. It will become uncomfortable to bear weight on the injured leg, and the patient will prefer to walk with assistive devices for added support, such as crutches or a cane. Sometimes, the patient may experience the knee “giving way” when stressed with simple activities such as walking or changing directions.

In the past, injuries to the ACL prohibited athletes from returning to “cutting” or “pivoting” high-demand sports. Currently, advanced surgical techniques reliably allow the return to athletic activities and physically demanding labor within 6 to 9 months. The goals of surgically reconstructing the ACL are to decrease the time lost to the injury, avoid additional injury to the knee, and to return to unlimited participation in functional and athletic activities. There are many different ways that the ACL can be reconstructed, and depending on the age, activity level, gender, and expectations of the patient.

| Click to Enlarge |

|

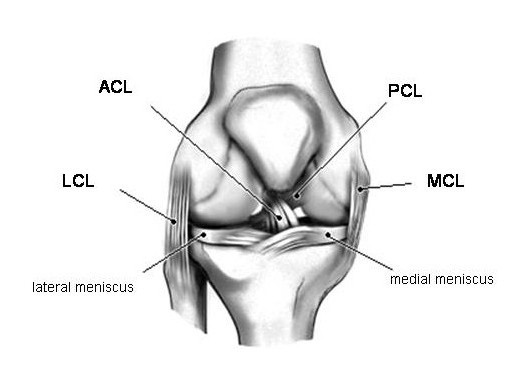

| Figure 1a - Drawing of a right knee as viewed from the front. The ACL helps to prohibit abnormal forward motion of the tibia under the femur. |

| Click to Enlarge |

|

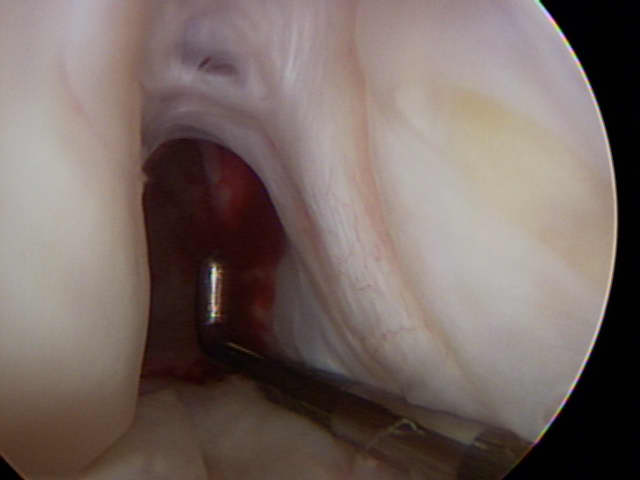

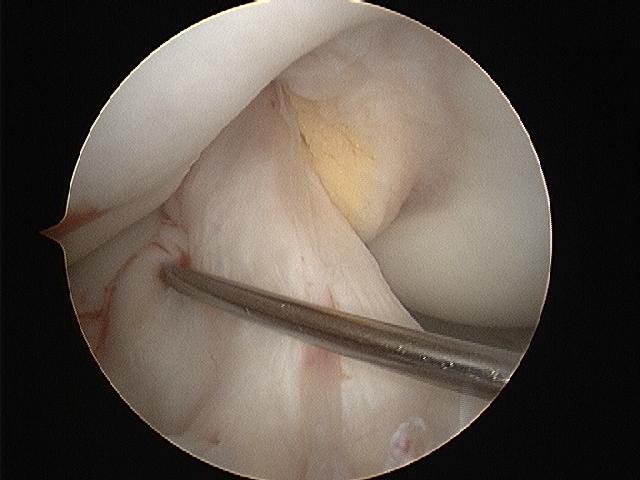

| Figure 1b - Arthroscopic view into the right knee. The metal probe sits across a normal-appearing ACL. |

| Watch Videos: Click to Play  Diagnostic Arthroscopy of an ACL-injured knee | Click to Play The technique of reconstructing the ACL with hamstring autograft |

Symptoms & Diagnosis

Characteristics of anterior cruciate ligament tears

There are several mechanisms that can cause injury to the ACL. Direct contact forces, such as those experienced in a motor vehicle accident, can cause ACL disruption. However, the ACL is most commonly injured by indirect, noncontact mechanisms such as vigorous cutting, landing, or twisting motions. An example of this would be an athlete who suddenly decelerates from running and makes a sharp cutting motion or when a skier catches their ski edge in the snow causing a rotational force at the knee.

At the time of ACL injury, individuals will experience a sudden severe knee pain and possibly hear or feel a “popping” sensation in their knee. Patients will have a difficult time bearing weight on the injured leg because of an unstable “giving out” sensation in the knee. Usually within the first few hours after the injury, the knee will become significantly swollen and the range of motion will typically decrease due to the limiting effects of pain and swelling.

A completely torn ACL will never heal back to it pre-injury “normal” state even after nonsurgical treatment such as rehabilitation and physical therapy. The ACL is contained within the joint and covered with a thin layer of tissue (synovium). This synovial tissue is in contact with synovial joint fluid in the knee. In order for healing to occur, a collection of blood must form and clot around the ligament, but once the ligament and synovial tissue are torn, the ligament will be bathed in synvoial joint fluid. The blood is not able to collect, as it is diluted and “washed” away by the joint fluid; therefore healing is unable to occur. In addition, even with a partially torn ligament, the mechanical function of the knee may be altered after an ACL tear such that the normal path of motion of the knee is altered (like a swing with one of the chains broken). It is very difficult for the ligament to resume a normal length and function in this setting.

Types

ACL injuries can be classified by the amount of damage to the ligament (partial or complete disruption). Injury to the ACL is usually a complete disruption, classifying it as a Grade III complete tear.

- Grade I Sprain - There is some stretching and micro-tearing of the ligament. The ligament is intact. The joint remains stable. These injuries rarely require surgery.

- Grade II Sprain (Partial Disruption) - There is some tearing and separation of the ligament fibers. The ligament is partially disrupted. The joint is moderately unstable. Depending on the activity level of the patient and the degree of instability, these tears may or may not require surgery.

- Grade III Sprain (Complete Disruption) - There is total rupture of the ligament fibers. The ligament is completely disrupted. The joint is unstable. Surgery is usually recommended in young or athletic persons who engage in cutting or pivoting sports.

Additionally, injury can be classified by the presence or absence of associated damage to other structures in the knee (isolated or combined). Combined injuries may involve damage to the menisci, stabilizing collateral ligaments, or other knee structures. Figure 1.

- Meniscus - The medial and lateral menisi are “cushions” between the tibia and femur that act as a shock absorber and distribute stresses placed on the knee joint. Additionally, this structure helps stabilize the knee. A meniscus tear typically occurs with twisting motions such as pivoting.

- PCL - The posterior cruciate ligament “crosses” behind the ACL and restrains the tibia from moving backwards (posterior) on the femur. Traumatically, this ligament is commonly injured by striking the upper tibia, causing the tibia to move backwards, thereby stretching or tearing the PCL. An example of this would be striking the upper tibia on the dashboard during an automobile accident. In athletics, a PCL will tear during a hyperextension or extreme hyperflexion injury (like falling onto the shin with the knee bent and foot pointed).

- MCL - The medial collateral ligament provides stability to the inside aspect of the knee. This ligament is commonly injured when a medially (inward) directed force is applied to the outside of the knee, forcing the knee to twist in and the foot to twist out. Injury to this structure is common, but if it is an isolated partial disruption injury then it can typically be treated with physical therapy and bracing.

- LCL - The lateral collateral ligament imparts stability to the outside aspect of the knee. Isolated LCL injuries are infrequent, but when injured it is commonly due a lateral (outside) force applied to the inside of the knee.

It is not uncommon to hear the term “unhappy triad” associated with an ACL injury. This describes an ACL injury associated with a concomitant MCL injury and medial meniscus tear. This triad usually occurs when the ACL has been torn for a long time (‘chronic tear’). It is more common to tear the lateral (outside) meniscus after an ‘acute’ ACL tear.

Similar conditions

ACL injuries are usually not subtle and most individuals will know exactly when the injury occurred. There are conditions in the knee that can mimic a sense of instability, some operative and others non-operative:

- Isolated collateral ligament injury - Severe injury to any of the knee ligaments (ACL, PCL, MCL, LCL) can result in a sense that the knee does not behave normally.

- Meniscal tear - A torn fragment of the meniscal cartilage can become temporarily “trapped” in the joint, and produce a sense of “giving way” or “instability”.

- Arthritis/articular cartilage injury - A flap of cartilage, or a loose fragment of cartilage or bone in the knee will produce “locking” or “giving way” that may be likened to “instability”.

- Patellofemoral joint instability/dislocation - Dislocation of the kneecap off the front of the femur can often mimic the “pop” that is heard when an ACL injury occurs, and can result in pain, inflammation, and a sense of instability. This problem can frequently be treated non-operatively after the kneecap is re-located. In cases where the problem recurs, surgery may be warranted.

- Patellofemoral joint pain - Pain behind the kneecap from cartilage softening or wear will often manifest as a sense of “giving way” or temporary instability. This problem is almost always treated non-operatively.

Incidence and risk factors

Unlike the medial collateral ligament (MCL) or posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), tears of the ACL frequently require surgical treatment.

This injury is particularly common in athletic individuals who participate in sports that involve twisting, cutting, jumping, and sudden decelerations. These activities overload the strength and stability of the ligament, leading to an ACL tear.

This injury is predominant in female athletes. It is believed that women are at greater risk than men because anatomical differences put the female knee at a mechanical disadvantage. Some of the distinctions that have been implicated in this phenomenon include having a wider pelvis, greater “knock-kneed” alignment, differences in the shape of the knee joint itself, delayed muscle reaction, and decreased muscle force. Additionally, hormones may play a role in ACL injuries in women. The change in hormone levels may influence the amount of laxity (looseness) in the ACL which predisposes it to disruption.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ACL injuries can usually be accurately diagnosed by clinical examination of the knee. A skilled examiner can usually evaluate the knee joint in a painless manner and discern if the ACL has been injured. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a painless study that will give an extraordinary amount of information in regards to the degree of injury to the ACL (partial versus complete), the location of the tear within the ligament, and if there are any associated injuries in the joint (isolated versus complex).

Treatments

Medications

There are no medications that can be used to heal a disrupted ACL. However, some medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) will help ease the pain or symptoms related to the meniscus deficient knee.

For any medications taken, patients should be aware of:

- The risks associated with the medication

- The possible interactions with other drugs

- The recommended dosage

- The cost

Exercises

After visiting the orthopedic physician, it might be advised that the patient meet with a physical therapist to increase the knee range of motion, decrease the amount of swelling, and maintain muscle control. Physical therapy and at home exercises will become part of the patients daily routine, whether the patient has the ACL reconstructed or not.

In rare cases or in sedentary individuals, there may be a role for non-operative treatment and rehabilitation. Non-operative treatment should be considered in:

- Patients with partial injuries and/or relatively stable knees on examination, who can perform their expected activities of daily living without difficulty

- Patients who were not capable of walking prior to the injury

- Patients who can not undergo surgery safely

Possible benefits of arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament (acl) reconstruction

The ACL is vital for “normal” knee function and surgical reconstruction can successfully restore this function.

The overwhelming majority of patients who undergo arthroscopic ACL reconstruction to address knee instability will have a successful result. This success is seen in patients who can participate in not only daily life activities but also in demanding physical activities such as competitive sports.

Who should consider arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament (acl) reconstruction?

The ultimate decision to surgically reconstruct the ACL depends greatly on the patient’s post-injury knee stability, ability to carry out activities of daily living, activities and athletic endeavors, and expectations to return to such activities.

Arthroscopic ACL reconstruction is considered when:

- The patient is a young individual or athlete who will be at significant risk for disability and/or further knee injury if normal knee mechanics are not restored

- The episodes of instability are a significant problem for the patient, and inhibit his or her ability to perform the activities of daily living, sporting activities, or job-specific requirements

- The patient has truly exhausted non-operative treatments, like physical therapy, and are still having frequent giving-way episodes, instability, and an inability to perform the usual activities of daily living or walk without assistive devices such as crutches or a brace

- There is concomitant injury to other structures in the knee

- The patient is sufficiently healthy to undergo the procedure

- The patient understands and accepts the risks and alternatives to the procedure

- An appropriate and comprehensive diagnostic evaluation has been performed and the nature of the problem is clear

- The surgeon is experienced and familiar with the techniques and treatments for arthroscopic ACL reconstruction

- The patient is capable and willing to comply with a comprehensive post-operative physical therapy program

Even if a patient believes their knee instability is minimal (they are not having frequent “buckling” episodes), the knee will still incur “wear and tear”. This will essentially lead to osteoarthritis by roughening the joint surfaces, adding additional forces to the menisci and thereby damaging this tissue. Other stabilizing ligaments in the knee will be stressed as they compensate for additional forces that the intact ACL would typically act against.

What happens without surgery?

For individuals who choose to not have surgery, rehabilitation of the injured knee is frequently recommended. In order to restore as much function as is possible; a rehabilitative treatment program may help to prevent instability and “giving way” episodes. Rehabilitation will focus on strengthening the muscles around the knee in order to provide better support, control, and stability.

There is nothing inherently dangerous about a mildly unstable knee so long as the patient is able to be adequately braced and willing to use appropriate assistive devices (cane, crutch, or walker) that will prevent falls or further injuries. This may require significant changes in lifestyle and activities to reduce the risk of instability events. For instance, an individual may have to avoid activities such as basketball or soccer and participate in non-impact activities such as biking or swimming for fitness. The goal is for patients to find activities where the knee feels stable and is pain free.

A minority of patients will continue to have instability to the degree that they are unable to walk or put weight on the extremity without it buckling on them. These persons are best served by surgery to stabilize the knee and restore function.

With or without surgery, a knee that has an ACL injury is at risk to develop osteoarthritis in the knee over time. Even a perfectly performed surgery cannot restore absolutely ideal knee kinematics. However, the arthritis usually takes years to develop if the mechanics of the knee are optimized.

Surgical options

Patients should be aware that there are different grafts available for use when reconstructing the ACL. Due to the uniqueness of each knee and injury from person to person it is best to discuss the different possibilities with an appropriately trained orthopedic surgeon.

What is the difference between ‘repair’ and ‘reconstruction’?

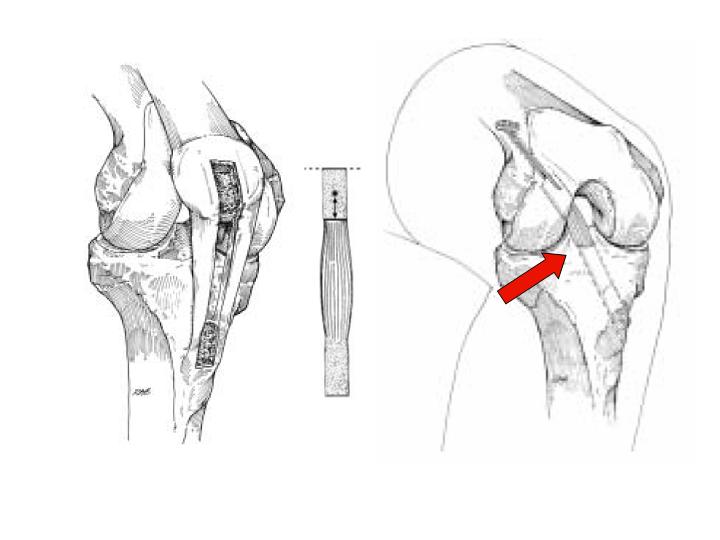

A surgical ‘repair’ of the ACL alludes to the ability to leave the injured ligament in place and attempt to ‘fix’ it back to the tibia or femur from which it has torn. In rare cases, the ligament will have pulled off of the bone (occasionally taking a small piece of bone with it). In such cases, the surgeon can suture the ligament or screw the avulsed bone back down and restore some if not all of the ligament function. However, the torn ACL is rarely able to be “repaired” because during most tears, the ligament tears at its midpoint (like a frayed rope). Over time, the ligament may become completely absent. Figure 3. Even if partially intact, the torn ACL sustains a degree of tissue damage and repair of the original ligament tissue has shown to provide relatively poor functional results.

‘Reconstruction’ of the ACL alludes to ‘substituting’ for the ligament by providing a new ligament. In reality, the surgeon creates a soft tissue substitute called a “graft” that reestablishes knee stability and provides a scaffold. Miraculously, the patient’s body will recognize this graft scaffold, populate it with living cells, and permanently attach it in place. Over a relatively short time (about 4 to 6 months) this new ‘ligament’ takes on the appearance and function of the normal ACL. The functional results of ACL reconstruction are predictably excellent, and the overwhelming majority of patients are able to get back to the same or higher degree of athletic activity without pain or instability. Figure 2, Video 2.

Where does the ‘graft’ come from?

Because the tissue graft is really serving as a temporary scaffold, there are many different options. In general, there are 2 categories of grafts: those that are taken from elsewhere in the patient’s body (called autograft) and tissues that are donated from persons who are organ donors (called allograft). In addition, there are several different anatomic sources of ‘autograft’ and ‘allograft’. There is no absolute “right” choice for graft, and the decision is usually based on various patient factors and the surgeon’s preference. Each has advantages and disadvantages that will be discussed below.

Patellar Tendon Autograft

The ‘bone-patellar tendon-bone’ autograft, or “BPTB” is a widely used source for ACL reconstruction. In general, the surgeon takes the middle 1/3 of the patellar ligament that runs from the bottom of the kneecap (patella) to the front of the tibia. This graft is ‘harvested’ with bone blocks from the patella and tibia respectively. These bone blocks can then be secured into bone tunnel ‘sockets’ that are placed at the anatomic location where the ACL originates on the femur (the ‘origin’) and the anatomic location where the ACL ends at the tibia (the ‘insertion’). BPTB autograft has been used for a long time and has an established track record. The body heals the bony portions of the graft to bone, and the ligament between serves as the substitute ACL. Advantages of this graft include its stiffness, strength, and low re-tear rate. It is also rapidly incorporated into the patient. Potential disadvantages include temporary or permanent pain at the front of the knee, slight motion losses, and a more difficult/painful early postoperative course. Figure 4.

Not all surgical cases are the same, this is only an example to be used for patient education.

Hamstring Tendon Autograft

Five hamstring tendons help to flex the knee. It is possible to use one or two of these tendons, from the inner part of the knee to reconstruct the ACL. Hamstring autograft has also been in use for a long time and has a very good track record. There is no bone harvested with the hamstring tendons, and therefore the harvest is easier for the patient with respect to pain. While the hamstring tendons used are technically stronger than the BPTB construct, the methods to fix the soft tissue graft into the sockets is generally less stiff. Advantages to hamstring grafts are that they are strong, easy and relatively painless to remove, and do not result in long-term knee pain. Disadvantages include the fact that the reconstructed ligament may not be quite as stiff, they are slower to incorporate, and there is controversy about whether there may be a slight loss in total hamstring strength after they are harvested. For many surgeons, this is the graft of choice. Figure 5a-b.

Not all surgical cases are the same, this is only an example to be used for patient education.

Quadriceps Tendon Autograft

A ‘hybrid’ graft is the quadriceps tendon autograft. This graft uses a bone plug from the upper kneecap and some of the tendon soft tissue from the quadriceps (thigh) muscle tendon at the knee. This graft is not as widely used, but has a very reliable track record. Advantages are that the quad tendon graft probably results in little long-term knee pain, it is strong, and uses bony healing at one end. Disadvantages are that it is slightly more painful to harvest in the short term, and may not be as stiff as the BPTB.

Not all surgical cases are the same, this is only an example to be used for patient education.

Allograft

Allograft is donated tissue from organ donors. There are many different sources of donor tendons and ligaments that can be used for ACL reconstruction. In addition to allograft BPTB and hamstring and quadriceps tendon, other grafts are also used, such as the tibialis anterior and tibialis posterior. Advantages to allograft is that they do not require the harvest of normal tissues from the patient with the ACL tear, so there is no “donor site” pain. The grafts are also typically robust and strong. However, there are theoretical risks of disease transmission from the donated tissue. Nationally, this risk is about 1:1.5-million for the transmission of HIV, and about 1:470,000 for hepatitis. The donated allografts DO NOT result in a significant immune response, and the patient does not have to take medication or worry about “rejection”. Allografts have a slightly higher re-rupture rate than BPTB, hamstring, and quad tendon graft. They have been commonly used for revision (repeat) ACL reconstructions and the reconstruction of multiple ligaments, however, the predictably good results of allograft use have led many surgeons to use these grafts in primary ACL reconstructions, even in young athletes.

Not all surgical cases are the same, this is only an example to be used for patient education.

Are there different ways to reconstruct the ACL?

Aside from graft choice, the other major consideration for the patient and surgeon is whether to consider a “double bundle” ACL reconstruction. The native ACL controls both translation of the tibia under the femur in the front/back plane and also the rotation of the tibia. While the ACL is made of millions of small fibers, these fibers are generally arranged into two major “bundles”. One bundle is predominantly a translation stabilizer, and the other a rotation stabilizer. Some surgeons advocate the substitution of both of the separate bundles to control the translation and rotation more completely. The reason this is important is that the single-bundle ACL reconstructed knee is still prone to develop osteoarthritis over the long term. It is possible that this is because a single bundle can not restore normal mechanics to the knee. However, the theoretical advantages to double bundle reconstruction have not been proven in long-term studies. At our institution, we perform double bundle reconstructions when patients request them, and in special cases that are prone to rotational instability. Figure 6.

Effectiveness

In the hands of an experienced surgeon, arthroscopic ACL reconstruction (no matter what graft is used or what technique) is usually very effective at eliminating instability and restoring comfort and function to the knee of a well-motivated patient. The greatest benefits are often the ability to perform the usual activities of daily living and participating in sports or demanding activities without the fear of giving way, locking, or pain. As long as the knee is cared for properly and subsequent traumatic injuries are avoided, the benefits of the surgery should be permanent.

Urgency

Reconstruction of the ACL is not an emergency. It is actually recommended to wait at least a few weeks after the initial injury to allow the inflammation to decrease and for the patient to regain full knee range of motion. This will contribute to a more successful return of motion and muscle strength after the surgical procedure. Except in special cases, it is generally advised to rehabilitate the knee first, to see if instability becomes a true problem before considering ACL reconstruction.

Before surgery is undertaken, the patient needs to:

- Be in optimal health

- Understand and accept the surgical alternatives, options, risks and benefits

- Have considered, discussed and or attempted non-operative measures to treat the problem

- Have undergone a comprehensive examination that includes appropriate diagnostic images such as X-rays and MRIs to define any additional factors contributing to the problem

- Seek out a surgeon who is experienced in arthroscopic surgery and reconstructing the ACL

Risks

The risks of an ACL reconstruction procedure include but are not limited to the following:

- Infection

- Temporary or permanent injury to the nerves and blood vessels around the knee

- Excessive joint stiffness

- Pain

- Scarring

- Immune reactions to donated tissue or suture materials (very low risk)

- Disease transmission from the donated tissue (exceedingly low risk)

- Failure of the reconstructed ligament

- The need for additional surgeries

- Anesthesia

The experienced and cautious surgical team uses special techniques to minimize all the above risks. Although adverse events following this surgical procedure are rare, they can occur and are not completely eliminated.

Managing risk

Many of the risks of an ACL reconstruction can be effectively managed if they are promptly identified and treated.

- Infections may require a wash-out of the joint, and rarely removal of the implanted tissue.

- Blood vessel or nerve injuries are rarely caused by the surgical procedure. Most of theses injuries resolve spontaneously overtime, but occasionally such an injury may require surgical repair. It is common to have decreased sensation around the incision sites. This numbness may or may not entirely resolve in time.

- Excessive stiffness of the joint is rare in the person who is cooperative with the postoperative rehabilitation program, and most of the stiffness will respond to exercises.

- Pain is a likely response after a surgical procedure that can be treated with medications, rest, ice, and compliant rehabilitation. As healing progresses overtime, the pain will diminish.

- Individuals scar and heal differently, and it is inevitable that anyone undergoing a surgical procedure will have scars. To allow for proper healing and therefore less scarring, the patient should follow post-operative instructions provided by their surgeon on how to care for their incisions.

- The risk of disease transmission from donor tissue is very small, but cannot be disregarded. All potential donors undergo strict screening that meets the guidelines of the American Association of Tissue Banks and the Food and Drug Administration. The tissue is thoroughly tested for HIV (risk of contracting HIV through donor tissue is less than 1 in 1.67 million), hepatitis (risk of contracting hepatitis is less than 1 in 470,000), and other infectious diseases. The transplant is then prepared and processed to prevent the transmission of bacteria and viruses according to United States Federal guidelines.

If a patient has questions or concerns about the “normal” course after surgery, the surgeon should be informed as soon as possible and be available to explain the expected course and outcome.

Preparation

Surgical ACL reconstruction is considered for healthy and motivated individuals in whom instability interferes with normal function and activity.

Successful surgery depends upon a partnership between the patient and the experienced knee surgeon. When possible, patients should optimize their health to prepare for surgery. Smoking should be stopped prior to surgery, and be avoided altogether for at least three to six months following surgery. Any heart, lung, kidney, bladder, tooth, or gum problems and concomitant injuries to the skin or extremity should be managed before the surgery. Any active infections will delay elective surgery to optimize the benefit and reduce the risk of joint infection. The surgeon should be made aware of any health issues, including allergies and non-prescription and prescription medications being taken. Some medications will need to be stopped prior to surgery. For instance, aspirin and anti-inflammatory medications (Advil®, Motrin®, Aleve®, and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) should be discontinued as they will affect intra-operative and postoperative bleeding.

Before surgery, patients should consider the limitations, alternatives and risks to surgery. Individuals must recognize that the procedure is a process and not an event; the benefit of the surgery largely depends on the patient’s willingness to apply effort to rehabilitation after surgery.

Patients must plan on being less active and functional for 6 to 8 weeks after the surgery. Plans for necessary assistance need to be made before surgery. Patients will be able to walk with assistive devices (knee brace and crutches) immediately after surgery. Jogging activities are rarely resumed before 15 weeks. A full return to cutting sports is usually possible by 6-months.

Timing

There is not a definite time period that should be considered before undergoing an arthroscopic ACL reconstruction. When considering when to perform ACL reconstruction, it is not usually defined by time, but rather by the condition of the knee. If the knee has significant inflammation or decreased range of motion, then it is recommended to delay the surgery until these factors have been remedied with pre-operative rehabilitation.

Additionally, it is best to not wait for an extended period of time before undergoing an ACL reconstruction. Since the knee is most likely “unstable”, it is important to reduce the occurrence of injury to other knee structures such as the menisci, collateral ligaments, and articular cartilage. Additionally, a chronically unstable knee can predispose an individual to early arthritis. However, it must be noted that the arthritis can not necessarily be avoided by ACL reconstruction.

Costs

The surgeon’s office should provide a reasonable estimate of the:

- Surgeon fee

- Hospital fee

- Degree to which these services should be covered by the patient’s insurance

Surgical team

Patients should inquire as to the specific training the surgeon has undergone to perform such procedures (i.e. a fellowship-trained, sports medicine specialist familiar with arthroscopic techniques and equipment). In addition, it is useful to know how many of these procedures the surgeon and the medical center perform on a yearly basis.

The surgical team of an experienced, specially trained orthopedic surgeon and certified physician assistant (PA-C) can dramatically improve the quality of care received by the patient. The interdependent physician-PA team ensures continuity of patient healthcare, commitment to personalized treatment, and makes certain patients will have greater access to care. The goal of this team is to magnify the efficiency and safety in the operating room and clinic, and to make certain the patient in receiving superior and quality care.

Finding an experienced surgeon

While surgeons who are capable of performing simple arthroscopic procedures are relatively easy to find, reconstructive surgeries in the knee demand a degree of highly specialized training. Many capable surgeons will have completed a fellowship (additional year or two of training) specifically in arthroscopic techniques, knee surgery and sports medicine. A qualified sports medicine surgeon should be comfortable with arthroscopic techniques, autograft harvesting, and tailor the appropriate treatment to the problem to be addressed. It is helpful to find a surgeon who is familiar with a number of different reconstruction techniques (single- and double-bundle) and graft types (hamstring, bone-patellar tendon-bone, quadriceps, and allograft). Fellowship-trained surgeons may be located through university schools of medicine, medical societies, or state orthopedic societies. Other resources include professional societies such as the American Orthopedic Society for Sports Medicine (AOSSM) or the American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS), Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA), and American College of Sports Medicine.

Facilities

Arthroscopic ACL reconstruction is usually performed in a qualified ambulatory surgical center or major medical center that performs such procedures on a regular basis. These centers have surgical teams, facilities, and equipment specially designed for this type of surgery. For those patients who require an overnight stay, the centers have nurses and therapists who are accustomed to assisting patients in their recovery from arthroscopic knee surgeries.

Technical details

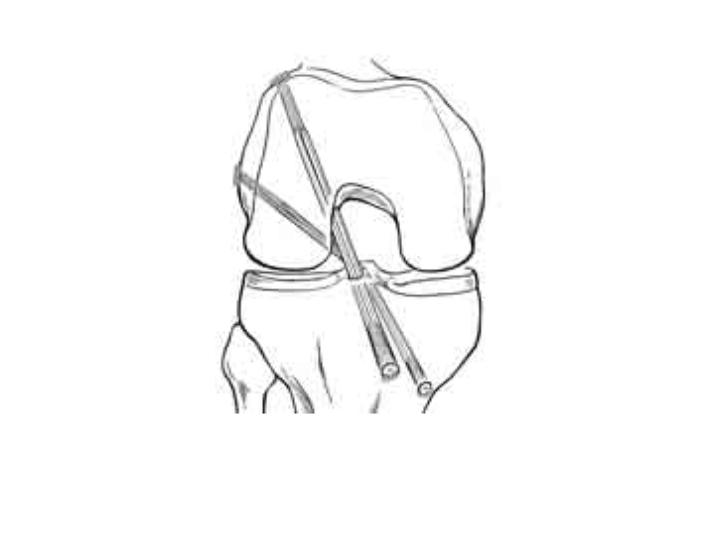

After the patient is comfortably positioned on the operating table and anesthetic has been administered, the surgeon begins by examining the knee while the patient is asleep. During this time the knee muscles are relaxed so the surgeon can assess the relative stability of the joint, the range of motion, and feel for any abnormal grinding or catching of the joint. The knee is then thoroughly washed and draped for surgery.

Next, three very small (1cm) incisions, or “portals” are made, at the front of the knee. Through these small incisions specially designed instruments and the arthroscopic camera can enter the knee. The knee joint is irrigated with sterile saline which “inflates” the joint with clear fluid.

Watch videos:

|

| Click to Enlarge |

|

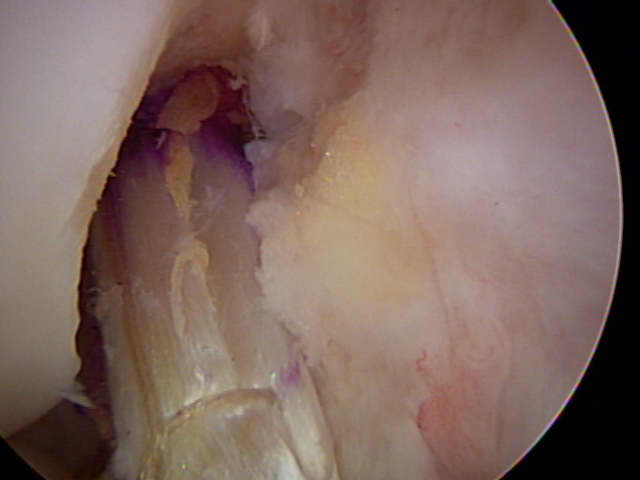

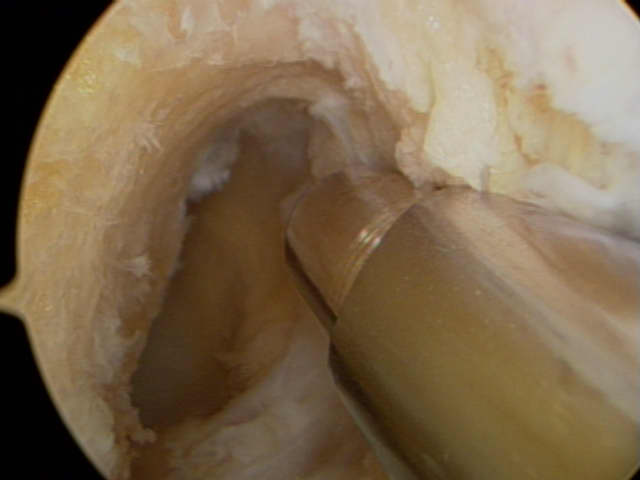

| Figure 7 - Arthroscopic view of a right knee. Special instruments are used to remove the residual ACL from the femur and tibia. |

The surgeon maneuvers the camera around the joint while he or she watches a video monitor of what the camera “sees”. A highly skilled surgeon can evaluate all of the important structures within the joint, test their stability and integrity, and look for signs of ligament injuries, cartilage wear (or arthritis), and bony injuries that can be caused by or lead to knee instability or mechanical grinding. Video 1. Most often, the surgeon will take photographs of the interior of the joint to help explain to the patient what was found, and how it was corrected. This portion of the surgery is called a “diagnostic arthroscopy” and is absolutely necessary to assure the success of any surgical procedure for knee instability. This is because the arthroscopic examination of the joint is still the “gold standard”, or best way to understand ALL of the factors that could be present and may need to be addressed to treat the problem.

Attention will then be focused on the ACL. The damaged ACL will be removed from the knee with special small instruments. Figure 7. Depending on the graft used, an incision will be made to harvest the graft and create the sockets for ACL reconstruction. The new tissue graft will be secured into two bone tunnel “sockets” in the femur and tibia so that it crosses the joint where the injured ligament used to belong. A surgeon who is comfortable with the anatomy of the joint and who has exceptional skills with specially designed arthroscopic instruments and implants can perform this surgery without the need for large incisions in a relatively short time. Other problems in the knee (meniscus tears, loose bodies, cartilage fragments, etc) can be addressed during the surgery for ACL reconstruction.

Immediately after the surgery, the patient is placed in a brace and starts ice therapy. Depending on the surgeon preference and other procedures performed, the patient can usually leave the hospital on crutches and weight-bear on the operated leg. Patients rarely need to spend the night in the hospital after an ACL reconstruction.

The early postoperative period is devoted to restoring motion and decreasing swelling in the operated knee. When motion is returning to normal and swelling is decreased, strengthening is begun and the patient is able to use an exercise bicycle usually within the first few weeks. By 6-weeks, a more intensive strengthening program is begun. By 15 to 18 weeks, when the strength is approximately 80% of the opposite leg, the patient is allowed to run on even, flat ground. Agility drills and sport-specific exercises and a cutting program are started at 20- to 24-weeks, and the patient is generally able to resume cutting athletics around 6-months. Surgeons differ as to whether a patient is required to wear a brace after surgery.

During the healing process, the body will organize the graft and attach it firmly to the bone tunnels. The tissue will repopulate with living cells. Incorporated grafts achieve their ultimate strength by about 24 weeks after the operation.

Anesthetic

There are two main types of anesthesia: general and regional. In general anesthesia, the patient is unconscious and has no sensation. A breathing tube will be inserted to ensure proper breathing. Patients will regain consciousness in the recovery room at the end of surgery.

Regional anesthesia (spinal and epidural anesthesia) involves an injection near a group of nerves between the bones in your back to numb the surgical area. The patient may remain awake or be sedated. The individual will not see or feel the actual surgery take place. This type of anesthesia will cause your leg and knee to be numb not only during the procedure but for several hours after the procedure.

It is strongly advised, that the patient discuss their preferences with the surgeon and anesthesiologist prior to surgery.

Length of arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament (acl) reconstruction

The procedure takes approximately 1 to 2 hours to complete. After the procedure, the patient can expect to spend 1 or 2 hours in the recovery room and anticipate going home on the same day of surgery.

Pain and pain management

The recovery of comfort and function following an arthroscopic ACL reconstruction continues over a few months. Initially, the knee must be protected with a postoperative brace, to prevent overuse or stressing the repair while the knee heals. Additionally, a very strict rehabilitation program will be initiated to provide the most favorable opportunity to heal without complications. Ironically, many patients who undergo this procedure will feel very comfortable long before the definitive healing has taken place, so strict adherence to the postoperative activity restrictions is critical.

Immediately postoperatively, the patient is given strong medications to help with the discomfort of swelling and the work of the surgery. Patients are discharged home with a prescription for oral pain medications.

Use of medications

Immediately postoperatively, pain medications are given through an intravenous (IV) line. The individual will be sent home with oral medication that is to be taken for pain control. Oral pain medications are rarely required after the first few weeks following the procedure.

Effectiveness of medications

Pain medications are very powerful and effective. The proper use of these agents lies in balancing their pain-relieving effects and their other, less desirable effects. Good pain control is an important part of appropriate postoperative management.

Important side effects

Pain medications (taken orally or through the IV) can cause drowsiness, slowness of breathing, nausea, vomiting, itching, allergic reactions, or difficulties in emptying the bladder or bowel. Patients who have been on pain medications for a long time prior to surgery may find that the usual doses of pain medication are less effective. For some individuals, balancing the benefits and side effects of medications is challenging. Patients should notify their surgeon if they have had previous difficulties with pain medications or pain control.

Hospital stay

Most patients do not require an overnight stay at the hospital after an ACL reconstruction. Generally, a person will spend one to two hours in the recovery room until the anesthetic medication has worn off.

When the patient is ready for discharge they will be instructed on the following:

- What home exercises are appropriate and how often to do them

- How to take the prescribed medications

- When and how to remove the postoperative dressing

- How to use the postoperative knee brace

- How to care for the operative knee and incisions

- How to recognized potential problems, and what is normal and abnormal

- Who to call if there are any concerns or questions

Recovery and rehabilitation in the hospital

The first two weeks after an arthroscopic ACL reconstruction are dedicated to controlling pain and inflammation, and resting.

Because fluid is used to expand the knee joint during arthroscopic procedures, the knee is frequently swollen for a few days following surgery. Also, the incisions will “weep” fluid for a couple of days postoperatively, and the dressing can become damp.

Generally, the patient can shower on the fifth postoperative day as long as the incisions are no longer draining. The area should be protected with plastic wrap and tape and should not be soaked in water. The patient should keep the incisions as dry as possible at all times until the sutures are removed.

The patient will be given a hinged knee brace. Unless otherwise directed by the surgeon, the patient will be able to bear as much weight as tolerated on the operative leg with the use of crutches and the brace. It is recommended to not engage in prolonged periods of standing, walking, or sitting over the first 7 to 10 days following surgery to eliminate and prevent swelling, pain, and stiffness.

In order to control pain and inflammation it is advised to use a Cryocuff or ice pack for 20 minutes every hour until your first post-operative visit, then as needed for pain relief. In addition, compression with an ace wrap that is not wrapped too tightly or thickly will provide relief. Finally, elevating the operative leg above the patient’s heart as much as possible for the first 3 to 4 days will help with swelling. It is strongly advised to elevate the leg with a pillow under the calf or foot, NOT under the knee.

For the first 2 weeks, a home program of rest and gentle range of motion and muscle control exercises are recommended. Typically at 14 days postoperatively a prescription for outpatient physical therapy will be provided and the progressive return to normal function will begin.

Physical therapy

Postoperative physical therapy for a reconstructed ACL is the standard of care. The primary objective is to provide a safe environment where the patient can return to normal function without compromising the integrity of the ACL repair. Rehabilitation will proceed through controlled phases involving a close working relationship between the physical therapist or certified athletic trainer and patient.

- 0 - 2 Weeks - For the first two weeks after surgery, therapy involves at home exercises that gently increase knee range of motion, control inflammation and pain, and achieve thigh muscle control. During this time, the patient will be allowed to weight bear on the operative leg with or without the assistance of crutches. It is imperative that the individual remains in the knee brace while walking.

- 2 - 6 Weeks - During this time, physical therapy will focus on preventing muscle atrophy (shrinking), maintaining and increasing range of motion, progressing to full weight bearing without crutches (while wearing the knee brace), and improving muscle control. It is usually possible to begin the use of an exercise bicycle during this time.

- 6 - 12 Weeks - In this stage of rehabilitation, the physical therapist or certified athletic trainer will provide exercises that increase muscle strength, stability, and endurance. Additionally, the patient will be working on balance and performing exercises on an elliptical machine.

- 12 - 24 Weeks - At this point in time the patient will be progressing to functional activities. Individuals can expect to be running around 15- to 18- weeks, and performing agility and cutting movements after 24 weeks.

Rehabilitation options

The results of physical therapy are optimized by a competent therapist familiar with ACL reconstructions and the usual expectations. In addition, a compliant patient who responsibly completes home exercises and is motivated to improve will enhance the recovery period. Most surgeons have a standard “protocol” that they give to physical therapist or certified athletic trainer to let them know how to rehabilitate the knee after an ACL reconstruction. It is important for a patient to find a therapist with flexible hours and in a convenient location because therapy will become a routine for several months. The surgeon can recommend a therapist with whom he or she is used to working and who is familiar with the procedure. Therapy is generally done on an outpatient basis, with 1 to 2 visits per week so that the therapist can check the progress, review, or modify the program as needed to suit the individual.

Usual response

Initially, there will be pain and swelling, but as this diminishes patients are almost always satisfied with the range of motion, comfort, and function that they achieve as the rehabilitation program progresses. Typically, in the later stages of rehabilitation, the patient feels comfortable enough that they want to progress faster, but a delicate balance must be found between how well the patient feels and a progression that does not disrupt the healing.

If the exercises remain or become painful, difficult, or uncomfortable, the patient should contact the physical therapist and surgeon promptly.

Risks

The greatest risks of rehabilitation entail the physical therapist or certified athletic trainer being too progressive, aggressive, or hesitant in achieving certain goals. This can result in failure of the procedure (re-injury to the ACL leading to knee instability), excessive knee stiffness, pain, or injury to associated structures in the knee. These problems are exceedingly uncommon and best prevented by communication between the therapist and surgeon concerning the short and long term expectations following this procedure.

Duration of rehabilitation

Every patient is slightly different in his or her progression through the rehabilitation, but it can be expected that the patient will be participating in rehabilitation for up to six months. Once the range of motion is acceptable and the strength has returned, the exercise program can focus on functional exercises that are applicable to the everyday life of the patient whether they are a cutting athlete, runner, or heavy laborer. This may require sport-specific or job-specific training with a physical therapist or certified athletic trainer.

Returning to ordinary daily activities

In general, patients are able to perform gentle activities of daily living starting 2 or 3 weeks after surgery. Most persons who work at a desk job can return to work during this time. The patient is strongly encouraged to continue wearing the functional knee brace.

The patient should be able to drive a vehicle when they are no longer taking pain medications, and when they can perform the necessary functions required for driving comfortably and confidently. A good question to answer prior to resuming driving is: “Would you want you driving if your 4-year old child was in the car or playing in the street?” If the answer to this is “no”, then it is strongly encouraged to refrain from driving at that point in time. In general it may take longer for a person to drive if the right knee was operated on because of the increased demands of pushing the gas and break pedal.

Long-term patient limitations

After completing a comprehensive rehabilitation program, that allowed the patient to regain full range of motion and strength, patients can return to physically demanding work and athletics without disability. Depending on whether there were concomitant injuries, many patients will return to cutting athletics at or above the level achieved before the ACL was torn.

Costs

The physical therapist should provide information of the usual cost of the rehabilitation program. Most insurance companies will cover the costs of some or most of the rehabilitation, except perhaps a “copay” that the patient must pay at each visit. Careful adherence to the home exercises between visits will usually decrease the overall number and frequency of visits required.

Summary of arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament (acl) reconstruction for anterior cruciate ligament - acl - tear

THE FIVE THINGS ONE NEEDS TO KNOW ABOUT ARTHROSCOPIC ACL RECONSTRCTION

- Not every person with an ACL rupture needs to have the ligament reconstructed.

- The surgery must be perceived as a process, not an event; there is a strict postoperative regimen that must be closely followed to assure the success of the procedure.

- In most cases, the combination of arthroscopic ACL reconstruction and physical therapy will re-establish a functional, comfortable, and stable knee that will allow a person to return to normal activities, demanding physical labor, and contact/impact sports such as running, soccer, football, basketball, and gymnastics.

- There are many different options for ACL reconstruction. The major issues involve the choice of graft (bone-patellar tendon-bone, hamstring, quadriceps, allograft, etc.) and the type of reconstruction (single-bundle or double-bundle).

- Post-operative physical rehabilitation is a critical and crucial part of the success of the procedure. A team approach by physician and patient almost always leads to a successful, satisfying result and a full return to activity.

127