Last updated: Monday, February 4, 2013

Standard radiographs can provide limited assistance in evaluating shoulder weakness.

Plain radiographs

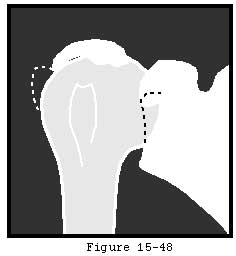

Small avulsed fragments of the tuberosity may be seen in younger patients with cuff lesions (see figure 1) (not to be confused with calcific deposits). Chronic cuff disease may be accompanied by sclerosis of the undersurface of the acromion (the "sourcil" or eyebrow sign) (see figure 2) traction spurs in the coracoacromial ligament from forced contact with the cuff and the humeral head and changes at the cuff insertion to the humerus (see figures 3-5). (Diamond 1964 Inman Saunders 1944 Johansson and Barrington 1984 Meyer 1931 Weiner and Macnab 1970b) Radiographs may also reveal evidence of some of the conditions possibly associated with cuff disease such as acromioclavicular arthritis chronic calcific tendinitis tuberosity displacement and the like (see figures 6-8). With larger tears radiographs reveal upward displacement of the head of the humerus with respect to the glenoid and acromion (see figures 9-12). (Colachis and Strohm 1971 Diamond 1964 Ismail Balakishnan 1969 Julliard 1933 Lilleby 1984 Weiner and Macnab 1970b) Kaneko et al (Kaneko DeMouy 1995) found that superior migration of the humerus and deformity of the greater tuberosity were the most sensitive and specific manifestations of massive cuff deficiency. In cuff tear arthropathy the humeral head may have lost the prominence of the tuberosities (become "femoralized") and the coracoid acromion and glenoid may have formed a deep spherical socket (become "acetabularized") (see figures 5 and 13-15).

Click to enlarge

Figure 14

A number of different studies are available for imaging the rotator cuff.

Deciding to order tests

Each of these tests adds both information and expense to the evaluation of the patient; health care resources can be conserved by only ordering imaging tests if the results are likely to change the management of the patient. Patients under the age of 40 without a major injury or weakness are unlikely to have significant cuff defects; thus cuff imaging is less likely to be helpful in their evaluation. At the other extreme patients with weak external rotation and atrophy of the spinatus muscles whose plain radiographs show the head of the humerus in contact with the acromion (see figures 16 and 17) do not need cuff imaging to establish the diagnosis of a rotator cuff defect. Finally the initial management of patients with nonspecific shoulder symptoms and an unremarkable physical examination is unlikely to be changed by the results of a cuff imaging test. Cuff imaging is strongly indicated when it would affect treatment such as in the case of a 47-year-old with immediate weakness of flexion and external rotation after a major fall on the outstretched arm or shoulder dislocation. Imaging the cuff is also important when symptoms and signs of cuff involvement do not respond as expected for example symptoms of "tendinitis" or "bursitis" that do not respond to three months of rehabilitation.

A review of the literature suggest that in experienced hands arthrography MRI ultrasound and arthroscopy each yield sufficient accuracy for making the diagnosis of a full thickness cuff tear. (Chiodi and Morini 1994 Crass Craig 1984 D'Erme DeCupis 1993 Grana Teague 1994 Mack Nyberg 1988 Owen Iannotti 1993 Paavolainen and Ahovuo 1994 Palmer Brown 1993 Quinn Sheley 1995 Robertson Schweitzer 1995 Tuite Yandow 1994 van-Moppes Veldkamp 1995 Wang Shih 1994)

Arthrography

For many years the single contrast shoulder arthrogram has been the standard technique for diagnosing rotator cuff tears. In this test contrast material is injected into the glenohumeral joint (see figure 18); after brief exercise radiographs are taken to reveal intravasation of the dye into the tendon (see figures 18 and 19) or extravasation of the contrast agent through the cuff into the subacromial subdeltoid bursa (see figure 21). In 1933 Oberholzer (Oberholtzer 1933) used air as a contrast agent injecting it into the glenohumeral joint prior to radiographic evaluation. Air contrast is still useful in those patients allergic to iodine. In 1939 Lindblom used opaque contrast opaque medium. (Lindblom 1939a Lindblom 1939b Lindblom and Palmer 1939) Since then iodinated contrast media have been the standard for single-contrast arthrography. A number of extensions of the basic technique have been published. (Ahovou Paavolainen 1984 Kerwein Rosenburg 1957 Killoran Marcove 1968 Neer 1983 Neviaser 1980 Resnick 1981 Samilson Raphael 1961)

Pettersson (Pettersson 1942) and Neviaser et al (Neviaser Neviaser 1994) demonstrated the effectiveness of arthrography in revealing deep surface partial-thickness cuff tears (see figures 19 and 20) however arthrography cannot reveal isolated midsubstance tears or superior surface tears. Craig (Craig 1984) described the "geyser sign" in which dye leaks from the shoulder joint through the cuff into the acromioclavicular joint. The presence of this sign suggests a large tear with erosion of the undersurface of the acromioclavicular joint (see figures 22 and 23). Double-contrast arthrography using both air and iodinated material may enhance the resolution of arthrography. (Ahovou Paavolainen 1984 Ellman Hanker 1986 Ghelman and Goldman 1977 Kerwein Rosenburg 1957) Berquist and associates (Berquist McCough 1988) reported on the use of single- and double-contrast arthrograms to evaluate the size of the cuff tears seen at surgery. Their ability to accurately predict one of four cuff tear sizes (small medium large and massive) was just over 50 per cent. The reported incidence of false-negative arthrograms in the presence of surgically proven cuff tears ranges from 0 to 8 per cent. (See references Hawkins Misamore 1985 Hazlett 1971 Mink Harris 1985 Neviaser 1971 Post Silver 1983 Samilson and Binder 1975 Wolfgang 1978.) The anatomical resolution of shoulder arthrography can be enhanced to a certain degree by obtaining tomograms with the contrast material in place to give information about the size and location of the tear and the quality of the remaining tissue. Further resolution can be obtained by performing double-contrast arthrotomography. (Freiberger Kaye 1979 Goldman Dines 1982 Goldman and Gehlman 1978 Kilcoyne and Matsen 1983) Kilcoyne and Matsen (Kilcoyne and Matsen 1983) used arthropneumotomography to evaluate the size of the cuff tear and the quality of the residual tissue. They found a good correlation with the surgical appearance.

The accuracy of arthrography does not seem to be enhanced by digital subtraction. (Farin and Jaroma 1995b)

The subacromial injection of contrast material (bursography) has been used to evaluate the subacromial zone and the upper surface of the rotator cuff. (See references Fukuda 1980 Fukuda Mikasa 1987 Lie and Mast 1982 Lindblom 1939a Lindblom 1939b Lindblom and Palmer 1939 Mikasa 1979 Nelson 1952 Strizak Danzig 1982) Fukuda reported six patients having normal arthrograms and positive bursograms which he defined as pooling of the subacromially injected contrast in the cuff tissue. He reported an overall accuracy for bursography of 67 per cent when compared with operative findings. Although lesions can be identified on this type of examination criteria for making diagnoses have not been rigorously defined.

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging can reveal information about the tendon and muscle. Seeger and coworkers (Seeger Gold 1988) and Kneeland and associates (Kneeland Middleton 1987) provided initial information on the use of magnetic resonance to image the cuff; however they did not document the sensitivity and selectivity of this method. Crass and Craig (Crass and Craig 1988) concluded that the accuracy of MRI in diagnosing cuff pathology is unknown. Kieft and associates (Kieft Bloem 1988) reported on 10 patients with shoulder symptoms evaluated with MRI and arthrography. Arthrography showed a tear in three patients whereas MRI detected none of them.

In a recent retrospective study by Robertson et al (Robertson Schweitzer 1995) the authors found that full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff can be accurately identified at MR imaging with little observer variation; however consistent differentiation of normal rotator cuff tendinitis and partial thickness tears is difficult. Iannotti et al recently described the sensitivity specificity and predictive value of MRI for different clinical conditions. (Iannotti Zlatkin 1991)

Ultrasonography

In experienced hands ultrasonography can noninvasively and non radiographically reveal not only the integrity of the rotator cuff but also the thickness of its various component tendons. In 1982 one of us (FAM) observed during prenatal ultrasonography that movement dramatically enhanced the resolution during real-time imaging of a fetal hand. Similarly adding a dynamic element to the sonographic evaluation of the rotator cuff significantly improves its resolution: moving the shoulder through even a small arc helps to distinguish the cuff tendons from the humeral head deltoid and acromion. The importance of movement during the ultrasound examination was recently reemphasized by Drakeford et al. (Drakeford Quinn 1990) Our initial series of ultrasound examinations of the shoulder was presented in 1983. (Farrer Matsen 1983 March 10-15) Since that time the criteria for diagnosing cuff lesions have evolved as have the quality of the equipment and the technique. Much of this work was carried out by and as a result of the stimulation of the late Lawrence Mack. (Mack and Matsen III 1995 Mack Matsen III 1985 Mack Nyberg 1988) He demonstrated that by careful positioning and by knowledge of the dynamic anatomy of the cuff the experienced ultrasonographer can image selectively the upper and lower subscapularis the biceps tendon the anterior and posterior supraspinatus the infraspinatus and the teres minor. Defects are revealed as absence of the normal tissue echoes and failure of the tissue to move appropriately with defined humeral movements (see figures 22 and 23). In his series of 141 patients from the University of Washington Shoulder Clinic (Mack Matsen III 1985) Mack demonstrateda specificity of 98 per cent and a sensitivity of 91 per cent in comparison to surgical findings. Most of the false-negative results occurred in patients found to have tears less than 1 cm in size. (Mack Matsen III 1985)

Ultrasonography has the advantages of speed and safety. In addition it provides the important benefit of practical bilateral examinations (which although theoretically possible with arthrography MRI and arthroscopy are usually not done for reasons of cost risk and time). Ultrasonography also allows the shoulder to be examined dynamically and provides the opportunity to show the results to the patient in real time. Yet another advantage is its low cost: a bilateral shoulder ultrasound is usually half the cost of a unilateral arthrogram and one-eighth the cost of a unilateral shoulder MRI. While some series have reported less accuracy with ultrasonography than arthrography others have pointed to its high degree of accuracy noninvasiveness and effectiveness in experienced hands. (Brenneke and Morgan 1992 Collins Gristina 1987 Crass and Craig 1988 Crass Craig 1984 Middleton Edelstein 1985 Middleton Reinus 1986a Middleton Reinus 1986b Olive and Marsh 1992 Paavolainen and Ahovuo 1994 Taboury 1992 Wiener and Seitz 1993) Ultrasonography has been applied to the evaluation of recurrent tears (Crass Craig 1986) as well as incomplete tears. (Crass Craig 1985) Seitz and coworkers (Seitz Abram 1987 Jan) compared arthrography ultrasonography and MRI for the detection of cuff tears in 25 patients. They found that ultrasonography was the most helpful study in accurately documenting the size and location of the tear when it existed. MRI suffered from problems of image resolution. Arthrography was reliable in determining full-thickness tears but correlation with size and location of the tear was difficult. Middleton (Middleton 1994) concluded that "Shoulder sonography is a valuable means of evaluating the rotator cuff and biceps tendon. In experienced hands it is as sensitive as arthrography and magnetic resonance imaging for detecting rotator cuff tears and abnormalities of the biceps tendon. Because sonography is rapid noninvasive relatively inexpensive and capable of performing bilateral examinations in one sitting it should be used as the initial imaging test when the primary question is one of rotator cuff or biceps tendon abnormalities."

In a recent review of the literature Stiles and Otte concluded that the accuracy of ultrasound in experienced hands was at least as good as that of MRI. (Stiles and Otte 1993)

Recent investigations have again confirmed the value of sonography. In a study of 4588 shoulders Hedtmann and Fett (Hedtmann and Fett 1995) found that the overall sensitivity in diagnosing cuff tears was 97% in full thickness tears and 91% in partial thickness tears. The false negative rate was less than 2% for an overall accuracy of 95%. The supraspinatus was involved in 96% the infraspinatus in 39% the subscapularis in 10% and the long head of the biceps in 34%. The authors also developed an approach for measuring the degree of retraction of the torn tendon. Farin and Jaroma (Farin and Jaroma 1995a) examined 184 patients for possible acute traumatic tears. Ultrasonography demonstrated 42 (91%) of 46 full-thickness tears and seven (78%) of nine partial-thickness tears. Ultrasonography showed more extensive tears than were found at surgery in four (4%) of 98 patients and less extensive tears in seven (7%) of 98 patients. Sonographic patterns consisted of a defect in 31 (63%) focal thinning in 10 (21%) and nonvisualization in 8 (16%).

Van-Holsbeeck et al (Van-Holsbeeck Kolowich 1995) found that a 7.5-MHz commercially available linear-array transducer and a standardized study protocol yielded a sensitivity for partial thickness tears of 93% and a specificity of 94%. The positive predictive value was 82% and the negative predictive value was 98%. Similar results are reported by others. (van-Moppes 1995) Hollister et al (Hollister Mack 1995) studied the association between sonographically detected joint fluid and rotator cuff disease. In 163 shoulders they found that the sonographic finding of intraarticular fluid alone (without bursal fluid) has both a low sensitivity and a low specificity for the diagnosis of rotator cuff tears. However the finding of fluid in the subacromial/subdeltoid bursa especially when combined with a joint effusion is highly specific and has a high positive predictive value for associated rotator cuff tears.

We find that expert ultrasonography provides the most efficient and cost effective approach to imaging of the cuff tendons. The real time dynamic and interactive examination of the rotator cuff provides the physician and the patient with the information needed to make the necessary management decisions in both primary and post surgical cuff conditions.