Last updated: Wednesday, January 26 2005

Traditionally it is stated that rotator cuff tears must be differentiated from cuff tendinitis and bursitis and that tests such as arthrography or ultrasonography are necessary to make this distinction. About rotator cuff tear diagnosis Perhaps a more realistic view is that many of the symptoms often attributed to tendinitis and bursitis are in actuality episodes of acute fiber failure that are not clinically detected. | | Click to enlarge |  | | Figure 1 |

|

|

|

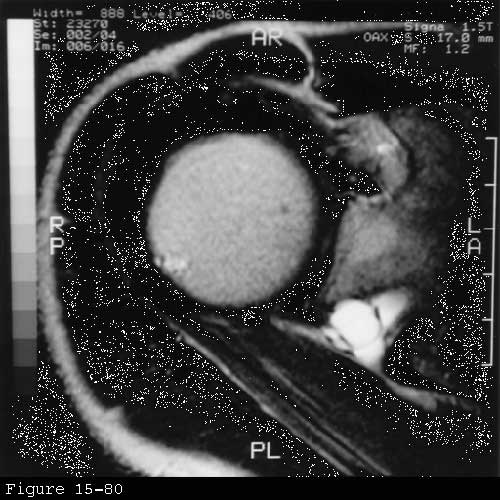

Patients with a frozen shoulder demonstrate by definition a restricted range of passive motion with normal glenohumeral radiographs. Patients with partial-thickness cuff defects may similarly demonstrate motion restriction whereas patients with major full-thickness defects usually have a good range of passive shoulder motion but may be limited in strength or range of active motion. An arthrogram in the case of frozen shoulder shows a diminished volume and obliteration of the normal recesses of the joint. Snapping scapula may produce shoulder pain on elevation and a catching sensation somewhat reminiscent of the subacromial snap of a cuff tear. However the latter can usually be elicited with the scapula stabilized while the arm is rotated in the flexed and somewhat abducted position. Scapular snapping usually arises from the superomedial corner of the scapula producing local discomfort and is elicited on scapular movement without glenohumeral motion. Glenohumeral arthritis may also produce shoulder pain weakness and catching. This diagnosis can be reliably differentiated from rotator cuff disease by a careful history physical examination and roentgenographic analysis (see figure 1). Acromioclavicular arthritis may imitate cuff disease. Characteristically however the shoulder is most painful with cross-body movements and with activities requiring strong contraction of the pectoralis major. Tenderness is commonly limited to the acromioclavicular joint. Relief of pain on selective lidocaine injection and coned-down radiographs may help establish the diagnosis of acromioclavicular arthritis. Suprascapular neuropathy and cervical radiculopathy are common imitators of cuff disease. The suprascapular nerve and the fifth and sixth cervical nerve roots supply two of the most important cuff muscles: the supra and infraspinatus. Thus patients with involvement of these structures may have lateral shoulder pain and lack strength of elevation and external rotation. In the presence of weakness the neurologic examination should test the cutaneous distribution of the nerve roots from C5 to T1. The biceps reflex and the triceps reflex help to screen C5/6 and C7/8 respectively. The next component of the neurologic examination requires recognition of the segmental innervation of joint motion: abduction C5 adduction C6 7 and 8. External rotation C5 internal rotation C6 7 and 8. Elbow flexion C5 and 6 elbow extension C7 and 8. Wrist extension and flexion C6 and 7. Finger flexion and extension C7 and 8. Finger adduction/abduction T1. |

A set of screening tests checks the motor and sensory components of the major peripheral nerves. Screening tests - the axillary nerve (the anterior middle and posterior parts of the deltoid and the skin just above the deltoid insertion);

- the radial nerve (the extensor pollicis longus and the skin over the first dorsal web space);

- the median nerve (the opponens pollicis and the skin over the pulp of the index finger);

- the ulnar nerve (the first dorsal interosseous and the skin over the pulp of the little finger); and

- the musculocutaneous nerve (the biceps muscle and the skin over the lateral forearm).

| | Click to enlarge |  | | Figure 2 |

|

|

|

The long thoracic nerve is checked by having the patient elevate the arm 60 degrees in the anterior sagittal plane while the examiner pushes down on the arm seeking winging of the scapula posteriorly. The nerve of the trapezius is checked by observing the strength of the shoulder shrug. Lesions of the suprascapular nerve produce weakness of elevation and external rotation without sensory loss.

Clinical conditions Clinical conditions affecting these structures include: - cervical spondylosis involving C5 and C 6

- brachial plexopathy involving the suprascapular nerve

- traction injuries (as in the mechanism of an Erb's palsy)

- suprascapular nerve entrapment at the suprascapular notch

- pressure on the inferior branch of the msuprascapular nerve from a ganglion cyst at the spinoglenoid notch

- traumatic severance in fractures or

- iatrogenic injury.

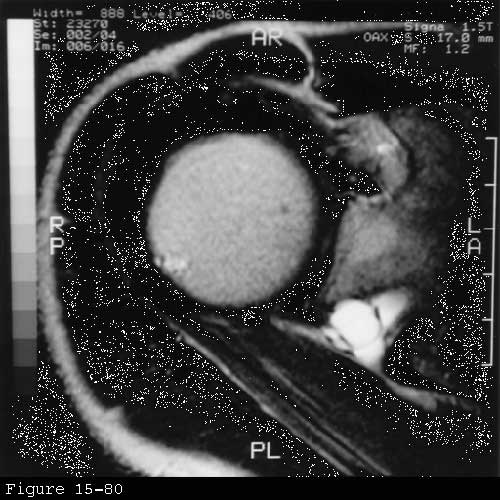

(Bacevich 1976 Bauer and Vogelsang 1962 Brogi Laterza 1979 Clein 1975 Donovan and Kraft 1974 Drez 1976 Edeland and Zachrisson 1975 Esslen Flachsmann 1967 Gelmers and Buys 1977 Jackson Farrage 1995 Komar 1976 Kopell and Thompson 1963 Macnab 1973 Macnab and Hastings 1968 Murray 1974 Picot 1969 Rask 1977 Rengachary Neff 1979 Schilf 1952 Schneider Adams 1985 Solheim and Roaas 1978 Strohm and Colachis 1965 Weaver 1983) Cervical spondylosis involving the fifth and sixth cervical nerve route may imitate or mask rotator cuff involvement by producing pain in the lateral shoulder as well as weakness of shoulder flexion abduction and external rotation. Cervical radiculopathy is suggested if the patient has pain on neck extension or on turning the chin to the affected side. Pain of cervical origin more commonly includes the area of the trapezius muscle along with the area of the deltoid and may radiate down the arm to the hand. Sensory motor or reflex abnormalities in the distribution of the 5th or 6th cervical nerve root provide additional diagnostic support for the diagnosis of cervical radiculopathy. Inasmuch as many asymptomatic patients have degenerative changes at the C5--C6 area cervical spine radiographs are not a specific diagnostic tool. When mild cervical spondylosis is suspected it is practical to implement a rehabilitation program without an extensive diagnostic workup. This program includes gentle neck mobility exercises isometric neck-strengthening exercises home traction and protection of the neck from aggravation positions during sleep If the condition is unresponsive or severe additional evaluation by electromyography and/or MRI may be indicated. Suprascapular neuropathy is characterized by dull pain over the shoulder exacerbated by movement of the shoulder weakness in overhead activities wasting of the supra and infraspinatus muscles weakness of external rotation and normal radiographic evaluation. This condition may arise from suprascapular nerve traction injuries suprascapular nerve entrapment brachial neuritis affecting the suprascapular nerve or a spinoglenoid notch ganglion cyst. The first three should involve the nerve supply to both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus and are most easily differentiated by the history. Traction injuries to the suprascapular nerve are usually associated with a history of a violent downward pull on the shoulder and may be a part of a larger Erb's palsy-type injury to the brachial plexus. Suprascapular nerve entrapment may produce chronic recurrent pain and weakness aggravated by shoulder use. Finally brachial neuritis often produces a rather intense pain lasting for several weeks with the onset of weakness being noted as the pain subsides. A spinoglenoid notch ganglion usually arises from a defect in the posterior shoulder joint capsule and may press on the nerve to the infraspinatus as it passes through the notch. These cysts are well seen on MRI (see figure 2). Depending on the site of the suprascapular nerve lesion electromyography may indicate involvement of the infraspinatus alone or involvement of this muscle along with the supraspinatus. None of these conditions should produce cuff defects on shoulder ultrasonography or arthrography. |