When Cancer Spreads to the Bone: Surgery for Metastatic Bone Disease

Last updated: Thursday, August 13, 2009

Overview

Basics of metastatic bone disease

Metastatic bone disease is a serious condition in which cancer has migrated from another part of the body, such as the lung, breast, prostate, thyroid, or kidney into one or more bones of the skeleton. Metastatic bone disease is not the same as cancer that originates in the bone, such as sarcoma. As a consequence, treating metastatic cancer that has gone to the bones is different than treating cancers that originate in the bones. Any kind of cancer can spread to the bone, but the most common are cancers of the kidney, thyroid, lung, breast, and prostate.

Immediate medical attention

Any new bone or joint pain should be taken very seriously in a patient who has a history of cancer, even if the cancer appeared to be in complete remission many years ago. Metastatic bone disease is heralded by onset of pain, usually in the arm, leg, back, or pelvis. Sometimes patients don’t know they have cancer until it spreads to the bone and causes enough pain that they seek medical attention. The physician then needs to find the original location of the cancer elsewhere in the body.

Facts and myths

Treating metastatic bone disease may not increase the length of time a patient lives, but frequently can increase the patient's quality of life. Radiation is used for pain control. Radiation doesn’t restore the integrity of the bone, and the patient may continue to be susceptible to fractures. Surgery can sometimes help protect the bone and make it easier for the patient to move around. The reduction of pain and the restoration of some activities, like walking, can improve a patient’s overall quality of life. Some people also believe that surgery should not be performed if the patient has only a short while to live. On the other hand, some patients think surgery is worth enduring if it gives them even a few more months of a more active, less painful, life. The ultimate decision on what treatments to undergo is individualized on a patient-to-patient basis.

Symptoms & Diagnosis

Prognosis

The appearance of metastatic bone disease is very serious and can worsen a patient’s overall prognosis. Left untreated, it has a severe effect on the remaining quality of life. A patient can become profoundly hypercalcemic (have very high levels of calcium in the blood), which can be dangerous. When too much calcium is released into the bloodstream, the patient can become prone to gastrointestinal symptoms, psychiatric symptoms such as delusions, and kidney stones. If the cancer spreads from the bones to the lungs, the consequences can be fatal. In a few patients whose initial treatment was successful, metastatic bone disease can be a chronic problem. The patient may, for example, have an isolated problem in a leg bone, get it treated, and live several years before the disease reappears in the spine or arm.

Lethality

How lethal metastatic bone disease is depends on the patient’s original type of cancer and how much the cancer has spread. Widespread metastatic bone disease has a poor prognosis. However, the outlook may be better for those patients who have just one or two spots in their bones. Patients may find some peace of mind from knowing that not all patients with metastatic bone disease have a grim future. Medication and surgery can help keep the symptoms of the disease at bay and help permit a good level of activity.

Pain

Pain is usually what prompts the patient to seek medical attention. Rarely is metastatic bone disease an incidental finding during a routine exam. Patients usually describe the pain as body aches that occur during the night, and feel like a bad toothache.

Debilitation

How debilitating metastatic bone disease is varies from person to person, depending on which part of the skeleton is affected. For example, a metastasis that appears in the right arm of a left-handed person causes less trouble than if the patient were right handed.

Comfort

Metastatic bone disease will cause some degree of discomfort. The amount will vary from person to person. Radiation treatment, medications, surgery, and other pain management techniques can often make the patient more comfortable. Patients should let their doctors and nurses know if they are in pain, where it hurts, how severe it is, and how the pain is affecting their daily lives. Their doctors and nurses can then find ways to try to reduce the pain. More can be done today to lower the musculoskeletal pain from cancer than was available in the past.

Curability

While treatment may improve the patient’s comfort and function, reduce pain, and prevent additional suffering from fractures, treatment is rarely curative.

Fertility and pregnancy

Metastatic bone disease has no effect on fertility. However, because metastatic bone disease usually doesn’t occur until after age 40, most women who develop metastatic bone disease are no longer in their prime childbearing years.

Independence

Metastatic bone disease may lessen independence in a significant number of, but not all, patients. Some patients with metastatic bone disease have chronic pain that requires treatment with sedating medications. Those whose bones are affected in the lower part of the body may have difficulty walking. If the bones in the arms are affected, patients may have problems carrying out the daily activities of living, such as cooking, writing, cleaning, shopping, and personal care. Patients will likely have to stop working. Some will need to use a wheelchair to get around. Because of their restricted range of movement, and if they are taking narcotics to curb their pain, some patients will not be able to drive. The loss of independence may be especially difficult for cancer patients who felt they have gotten their daily life back and have been disease-free from cancer for 10 or 20 years, only to have their activities curtailed by pain and bone deterioration. However, surgery or radiation might be able to reduce the pain to the point where narcotics are not needed, and might be able to reduce other disabilities from the disease.

Mobility

The limitations that metastatic bone disease places on mobility depends on which bones have the disease, how many bones are involved, and how much area of each bone is damaged, and the severity of the damage. Patients should check with their doctor to see if treatment can help restore some of their lost mobility or reduce their risk of fractures.

Daily activities

Whether metastatic bone disease alters activities of daily living depends on where in the skeleton the disease is occurring. For example, metastasis in the arm bones or in the upper backbone may limit the ability to do housework, work at a computer, use hand tools, or do lifting. In addition, a patient’s energy for accomplishing tasks may be low, especially while he or she is receiving radiation.

Energy

As with many other forms of cancer, metastatic bone disease is often accompanied by fatigue. In addition, the narcotics to treat pain are often sedating. Radiation and chemotherapy can also cause fatigue, and patients often suffer from sleep problems, including being woken up by pain. This loss of nighttime sleep can lead to daytime drowsiness. Depression may also make it hard to get up the energy to do things. Some forms of cancer can cause anemia and its resulting tiredness. Some causes of fatigue, such as depression, anxiety, insomnia, and anemia, can be addressed to reduce its impact.

Diet

There are no specific diets, dietary restrictions, or requirements for people who have metastatic bone disease.

Relationships

A person who has metastatic bone disease may need more practical help, because the disease might have significant impact on his or her independence and mobility. A patient will likely have repeated visits to the doctor, which will take up a sizeable amount of time, especially if the patient lives in a rural town and must travel a long distance for treatment. Sometimes receiving cancer treatment, or caring for a relative with metastatic bone disease, can seem burdensome at times. For example, radiation therapy often requires several weeks of daily treatments at the hospital or clinic. If the patient already has stresses in his or her life, or has had difficult interpersonal relationships before the disease occurred, these may become worse because of the demands of living with cancer. On the other hand, sometimes the appearance of a serious disease can change people’s outlooks in such a way that family, friendships, and other personal relationships become more important and stronger.

Other impacts

Metastatic bone disease is not contagious, nor is it disfiguring. One of the impacts of the disease is that some patients will have metal surgical hardware placed in their body to treat a fracture or a bone about to fracture.

Incidence

Metastatic bone disease is more likely to occur in patients with a history of lung cancer, breast cancer, or prostate cancer. It is less likely to occur from cancers of the gastrointestinal system, such as colon cancer, stomach cancer, or pancreatic cancer. It is equally common in men and in women.

Acquisition

Metastatic bone disease occurs when cancer cells from another area of the body –the breast, the lung, or other organ – travel through the blood stream and attach themselves to bone. There are factors circulating in the blood stream that give cancer cells a predilection for setting up shop in bone. The skeleton is highly vascularized, that is, a lot of blood vessels feed into it. Living bone is not in the dry, unchanging state seen in the skeletons displayed in high school biology classes. Instead it is constantly remodeling itself. Its dynamic nature, with a lot of cell turnover, makes bone susceptible to invasion by cancer cells from elsewhere in the body.

Genetics

Genetics plays a role in a person’s risk of developing the original cancer in another part of the body. For example, certain genes put women at risk for breast cancer, some forms of breast cancer run in families, and breast cancer is more likely than some other forms of cancer to spread to the bone. However, metastatic bone cancer doesn’t run in families, and as yet no genes have been discovered that either place people at risk for metastatic bone cancer or protect them from it. Metastatic bone disease is usually a consequence of not being able to completely destroy the original cancer or the result of chemotherapy that failed or that was not fully effective.

Communicability

Metastatic bone cancer is not contagious. It cannot be spread from person to person.

Lifestyle risk factors

Certain behaviors, life factors, and habits can put people at greater risk for the kinds of cancers that might lead to metastatic bone disease, but not at greater risk for metastatic bone disease itself. For example, smokers are more likely to get lung cancer. Women who are obese or childless are at greater risk for breast cancer.

Injury & trauma risk factors

There is no evidence that injury or trauma leads to metastatic bone cancer.

Prevention

The only way to prevent metastatic bone disease is through good control of the cancer that originated elsewhere in the body.

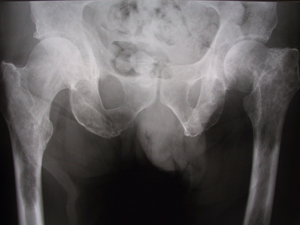

Anatomy

Metastatic bone disease is more likely to affect the parts of the skeleton that have a lot of red bone marrow. Examples are the bones in the hip, spine, and other bones near the midsection of the body. However, tumors can spread to any bone in the body.

Initial symptoms

Metastatic bone disease is signaled by the appearance of a new musculoskeletal pain that doesn’t go away, especially in a person who has had cancer. The pain may be mistaken for any number of things: a muscle injury or strain, or the patient may think he or she has unknowingly bumped the arm or leg, or slept in the wrong position. The pain may feel as if it is coming directly from the bones or joints, or the pain may feel as if it is coming from another location, like the muscles. It can also appear as a new pain in someone who has cancer elsewhere in the body, but who is unaware that he or she has cancer. Any new musculoskeletal pain in a person who has had cancer should be taken very seriously and imaged appropriately by a radiologist. An image as simple as an X-ray may tell whether that patient has metastatic bone disease.

Symptoms

The major symptom of metastatic bone disease is musculoskeletal pain. On an X-ray, a spot may be seen on a bone. Some forms of metastatic bone disease will cause bone deformity, others may cause parts of the bone to disappear. Either way, the quality of the affected bone is poor. Women who have breast cancer or who already have osteoporosis (bone loss from another cause) may be more badly affected.

Progression

Typically if metastatic bone disease is not treated, the symptoms will worsen. The patient may begin to have mobility problems, such as difficulty walking. If the backbone is affected, the patient may feel as if a nerve in the back is pinched, or feel pain shooting down the leg, or have other signs that the spinal cord is being compressed. Paralysis can occur if this is left untreated. The patient may suffer one or more broken bones after a slight fall or seemingly minor injury, because bones with metastasis are fragile. However, if metastatic bone disease is treated, the patient may see a remarkable diminution of pain, a lowered risk of fractures, and a restoration of function. The treatment will not prolong life, but it may make the quality of life better. The speed of progression of metastatic bone disease depends on the type of cancer that has spread to the bones, and on the individual patient. It is difficult to predict how quickly or slowly the disease will progress.

Secondary effects

Some of the secondary effects of metastatic bone disease are hypercalcemia (a problematic increase of calcium in the blood stream); anemia (a reduction in red blood cells); sedation, mental cloudiness, and other effects of narcotics; and an increased risk of falls and bone fractures.

Conditions with similar symptoms

Metastatic bone disease may initially be confused with pain from a muscle ache or sprain, when the real problem is skeletal from cancer, not muscular from an injury. Delays made from writing off the symptoms as being do to a muscle injury can profoundly impact the patient’s quality of life.

Causes

The underlying cause of metastatic bone disease is the spread of cancer from another organ or another type of tissue into the bone. The bone is an ideal environment for cancer cells to take hold and grow, because of factors in the circulating blood that allow cancer to adhere to the bone. The sheer amount of blood volume that passes through the bone increases the odds that the bones will be readily exposed to cancer cells traveling in the blood. While people usually think of cancer as being a disease of a particular site, such as the breast or the thyroid, it is actually thought to be a more systemic disease of the body, and can often be found in the blood stream. Cancer patients are given chemotherapy to remove cancer from the blood stream after surgery and radiation therapy have been performed to remove or destroy the original tumor.

Effects

Metastatic bone cancer can weaken or destroy bone tissue. This releases calcium into the blood stream, and also damages the ability of bone marrow to manufacture enough healthy, new blood cells. The affected bones might also fracture easily. The burden of cancer in the body, as well as the indirect effects of cancer in the bone, such as causing high levels of calcium and low blood cell counts, can become so great that the patient’s life is threatened.

Diagnosis

Cancer patients who are experiencing new pain that suggests the cancer may have spread to the bone, or new patients who have symptoms that suggest they may have an advanced stage of cancer that has not yet been diagnosed, may have images taken to see if cancer is appearing in their bones. Radiographic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be ordered if X-rays are inconclusive. MRI creates detailed anatomical pictures of the patient’s bones and soft tissues. The images are then examined to see if there is cancer in the bone, and if so, how much damage it has done. A patient might also have a bone scan to screen the entire skeleton for any possible cancer.

Diagnostic tests

Metastatic bone disease is generally diagnosed through imaging procedures, such as X-rays, MRI, or CT scans, to produce clear pictures of the bones to see if and how they are affected by cancer. In addition, the levels of calcium in the blood might also be measured through a blood test, and other tests, such as looking at the blood sample to see if the patient has anemia, might also be performed. These blood tests do not diagnose metastatic bone disease, but are used to check for conditions that might accompany the disease.

Effects

The imaging tests are not painful. Patients need to hold fairly still for the technician to obtain a clear image. A few patients are troubled by the confined space and the noise of the magnetic resonance imaging machine. Such patients should tell their physician or the imaging technician if they have a fear of closed spaces, to get advice on how to manage this feeling during the imaging. Much of the pain of diagnosis is emotional distress, as the patient deals with uncertainty and with the possibility that their cancer may have spread to the bone. Facing the possibility of metastatic bone disease can be a big emotional blow to someone who has been free from cancer for up to ten or 15 years, and who thought the cancer was potentially cured. How people find ways to come to terms with this situation varies from person to person.

Health care team

If the patient’s personal physician or oncologist suspects metastatic bone disease, they may conduct some preliminary exams and testing, and then refer the patient to a medical center or cancer treatment center. At a major medical center, the patient’s team will usually be made up of an internal medicine specialist, a medical oncologist, a radiation oncologist, a pain specialist, and an orthopedic surgeon, as well as nurses, technicians, and patient care coordinators. Cancer care centers that are part of major medical centers and cancer research institutions are ideal set ups for optimal care of metastatic bone disease because all specialties that treat cancer are represented, they work together as a team, and have experience in treating metastatic bone disease.

Finding a doctor

People who are suspected of having metastatic bone disease can be referred by their physician to a regional cancer treatment center, to a major medical center, or to an alliance of medical institutions that have joined together to diagnose and treat cancer patients. In many cases, patients can also refer themselves or a friend or family member to one of these centers. People can call a medical center, a cancer research institution, or an institution specializing in cancer care to learn if they have a special expertise in treating metastatic bone disease. Patients should be careful to look at the qualifications and reputation of any institution before becoming a patient of that center, and especially check the institution’s expertise in treating metastatic bone disease.

Treatments

Patients usually receive some combination of surgical, medical, and radiation treatment for metastatic bone disease. While this treatment is not curative, it may help improve the patient’s quality of life by reducing pain, making it easier to move around, and preventing or fixing bone fractures. Surgical treatment usually consists of implants of metal rods or plates to stabilize fractured bone or bone about to fracture. Surgery may also sometimes be performed to reduce compression on the spinal cord, if that is occurring and is causing pain, numbness, loss of bowel or bladder control, or difficulty walking or using the arms. Radiation therapy is directed at killing the cancer locally and at improving localized pain control in affected parts of the body. Medical treatment may include different forms of chemotherapy. A class of drugs called bisphosphonates act by decreasing bone destruction and thereby reducing pain. This class of drugs is similar to those used to treat osteoporosis, a form of non-cancerous bone loss common in postmenopausal women or in younger adults who diet and exercise in the extreme. Patients will also receive medications to boost their comfort, such as narcotics or other pain treatments. Surgery usually needs to be performed only once, radiation therapy usually takes a number of treatment sessions over several weeks, and medication of some sort usually continues for the rest of the patient’s life. After treatment, many patients go back to their regular lifestyle, and their primary-care doctor or oncologist at home manages their medications for them. At the UW and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, and at many other widely respected cancer treatment centers, every effort is made to keep the patient’s primary care physician and local oncologist informed on their patient’s clinical course.

Self-management

Any cancer patient should see their doctor early on if they are experiencing new pain, and not wait to schedule an appointment. Patients should keep their diagnostic and treatment appointments, and follow the course of treatment he or she has agreed upon with his or her cancer treatment team. Patients should take their medications as prescribed, or report intolerable medication side effects to their physician and not simply stop taking the medication without consulting a doctor or pharmacist.

Health care team

Health professionals involved in treating or managing metastatic bone disease may include medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, orthopedic surgeons, hospitalists, pharmacists, nurses, rehabilitation medicine specialists, physical therapists, social workers, and others as needed for the patient’s individual concerns. The patient’s primary-care physician will also continue to be involved in the patient’s care before and after treatment at a specialized medical center, and may be consulted during the course of specialized treatment.

Pain and fatigue

Radiation therapy can usually help reduce localized pain. Surgery can sometimes help prevent or reduce pain from fractures or stabilize bones that are at risk for fracture. Medications, such as narcotics, can also help in pain reduction. If anemia is a cause of fatigue, it can sometimes be treated. Adequate pain control can often prevent or relieve sleep problems and the daytime fatigue that results from repeated nighttime awakenings. Comfort items, such as a favorite chair; soft, easy fitting clothing; and a good mattress and pillows, can help to promote rest by reducing pressure on achy parts of the body.

Diet

No, diet has not yet been shown to help treat metastatic bone disease. Nonetheless, appropriate calcium and vitamin D supplementation can help maintain a healthy skeleton.

Exercise and therapy

Exercise can increase overall well being and keep bones healthy, but it should not be attempted until after the bones have received appropriate treatment and the patient has checked with his or her doctor before starting an exercise routine.

Medications

Patients may be given various forms of chemotherapy for the recurrence of their cancer. They may also receive medications similar to those given for osteoporosis (bone loss) to improve the quality of their bone tissue. They can also be given medications, such as narcotics, to control their pain. Other medications, such as treatments for anemia, may be prescribed as necessary to control other conditions that may accompany or occur coincidentally with metastatic bone disease.

Surgery

While not curative, surgery can help prevent or manage some of the problems associated with metastatic bone disease, and can prevent the bone from fracturing (breaking) or treat the fracture if it already has occurred. Rods, plates, joint replacements, and some types of cementing treatments may be employed surgically to strengthen weak bones or to prevent or fix fractures.

Joint aspiration

Neither joint aspiration nor injection is used in the management of metastatic bone disease.

Splints or braces

In selected cases, if a bone is broken or if a patient elects not to have bone surgery, splints or braces may be employed.

Alternative remedies

Alternative remedies for metastatic bone disease are directed at increasing patient comfort, not at treatment or cure. Some patients may try non-medical modalities or non-Western medical therapies in addition to their medical treatment to improve their sense of well being. These may include acupuncture, herbs, massage, and meditation. Some patients believe in the metaphysical nature of certain places to help them feel better. Patients should tell their physician about any herbal medicines they plan to take, because some may interact unfavorably with their other treatments. Some patients find that complementary, non-medical modalities such as meditation can be helpful, but it is very important also to seek conventional treatment for metastatic bone disease.

Long-term management

There needs to be continual monitoring of the original cancer that now has spread to the bone. Any musculoskeletal complaints from a patient need to be taken seriously by the patient and his or her physician. Depending on the type of cancer, many patients with metastatic bone disease will be on chronic medication management.

Unproven remedies

People need to realize that the treatment of metastatic bone disease is not curative. Many people think that if their bone disease is cared for, then they are cured. This is not true. Some patients also have a fear of radiation treatment, but today radiation therapy has evolved so the side effects are fewer and those that do occur are managed more effectively than they were 20 or 30 years ago

Strategies for coping

Having a good social support system is critical. Maintaining strong lines of communication with health-care workers is also helpful. If a patient feels depressed or anxious, he or she should consider seeking assistance from a social worker, hospital or clinic chaplain, psychologist, or psychiatrist, depending on the patient’s personal preferences for a counselor and his or her psychological needs.

Asking for help

Patients have different preferences for the kind of help that would be useful to them, as is also the case with their family members. Some patients and their families find it useful to talk about coping with the disease with the physician who is treating them, or with other health care personnel such as nurses or social workers or psychologists. Others prefer to talk with a general medical chaplain trained or one who is trained in counseling cancer patients. Some patients receive support through members of fraternal, social or other organizations to which they belong. There are also support groups offered through local chapters of the American Cancer Society or through various hospitals.

Work

Most people who develop metastatic bone disease are elderly and retired, or are not working because of the severity of their illness.

Family and friends

It is important for people who have metastatic bone disease to have a good support system in place, or to seek out a support group. Having others who can help can sometimes provide respite to family members or close friends who are the primary caregivers for the patient. Caring for a relative or friend who has metastatic bone cancer can be especially challenging for those living in rural areas, because of the distance needed to travel for medical appointments or for others to visit them to offer support. The subject of useful support for caregivers is one that needs more attention from health-care professional and from community service organizations.

Adaptive aids

Canes, braces, walkers may be of use under some circumstances, but the goal of most treatment plans is to try to return patients to a level where they don’t need assistive devices or aids. This doesn’t always work out every time, but it is the goal of treatment.

Stress

Patient should feel free to ask lots of questions of their physicians. They shouldn’t leave the clinic until all of their questions are answered. They might want to have a friend or family member along on doctor’s visits to record their conversations with their physician, because their anxiety is likely to be high and as such they may forget much of what is said. Physicians or other health professionals may know of support groups that can act as an outlet for patients or their family members to share their anxieties or experiences with other cancer patients or family members of cancer patients.

Resources

Patients can obtain information by calling their local chapter or the national office of the American Cancer Society. There are also libraries or patient information rooms at most cancer hospitals. Patients can also go to trusted Web sites, but should be aware that there is a lot of anecdotal information on the Web that may not conform to the general standards of care.

Condition research

Unfortunately, nationally there has not been sufficient research attention given to the problem of metastatic cancer generally. However, more studies are beginning to emerge.

Pharmaceutical research

Drugs aimed at treating bone loss and bone pain are the most recent development. There is also research to develop new narcotics and better pain control with fewer side effects.

Non-surgical research

There are no major research studies under way at the University of Washington in lifestyle issues or other non-medical, non-surgical contributors to metastatic bone disease.

Surgical research

There is research under way to develop optimal devices for stabilizing bones that have been weakened by cancer.

Cellular, genetics, or tissue research

There is new research aimed at understanding why cancer spreads to the bone and how cancer cells destroy tissue after they reach the bone. There are lots of different cellular factors that may play a role in how cancer cells attach to the bone and disintegrate the bone. If scientists can find out how the disease begins in the bone, perhaps they can develop ways to decrease the ability of cancer cells to attach to the bone to prevent metastatic bone disease.